VFX Supervisor Andrew Simmonds talks about leading the team at ReDefine, using volumetrically captured human assets to digitally create the massive crowds at Whitney Houston’s performances.

A critical element in the life and career of a superstar like singer Whitney Houston are the tremendous crowds that attended her concerts around the world. The producers of ‘I Wanna Dance with Somebody’, the recent biographical film about Whitney, knew those crowds had to be there on screen to make her story come to life. But knowing exactly how to create them would be a challenge, calling for the work of talented visual effects artists.

VFX studio ReDefine, based in London, was one of the vendors that took on this challenge. Led by VFX Supervisor Andrew Simmonds, the team at ReDefine used volumetrically captured human assets to digitally create the crowds at performances in massive concert venues including Wembley Stadium, Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy and Arena Nürnberger Versicherung. Here, Andrew tells about the decision-making, probelm-solving, techniques and processes involved in the project.

Previsualisation

ReDefine’s work on the project began with previsualisation. Production VFX Supervisor Paul Norris, liaising with the production, approached ReDefine to help with previs in January 2022. Together they looked over the layouts and interiors of the real stadiums, thought carefully about where the crowd should be relative to where the concert was staged, and decided how to fill the spaces.

They compiled as much information as possible ahead of the shoot, which got underway shortly after. Having a clear vision of how the crowds and performances would be handled benefited the production and ReDefine’s own team, as well as the cinematographers and crew.

Digital crowd replication was going to be essential, as were digital builds of the stadium interiors. Not only would a digital approach be more cost-effective than paying hundreds of extras, it also meant they could film in a generic stadium rather than a specific venue, reducing production costs further, as well as meet Covid regulations more easily.

Volumetric replication was the method chosen for the crowds at Whitney’s concerts. Paul Norris and the production read through the entire script and identified crowds and crowd movements within each sequence. They would decide, for example, whether the crowd in a particular stadium for a particular show should have a crowd on their feet or sitting, clapping their hands or cheering in a certain manner and so on. They methodically worked out a list of desired, typical moves, per venue, and compiled them into a library.

Volumetric Capture

That library was passed to Dimension Studio, whose job it was to capture and generate the individual crowd elements. The team at their local Washington DC partner studio, Avatar Dimension, individually shot 300 actors performing inside their video capture stage, shooting each one approximately three times with differing poses, props and costume, ultimately delivering almost 1,000 captures.

The stage is a closed volume, surrounded by green screen and measuring 8 feet in diameter, rigged with 70 cameras. 62 were in a cylindrical formation around the subject, with 8 overhead. Volumetric video captures human performance from all angles, and results in a 3D video, allowing the user to view any point of the performance from any angle.

Layout

Final Composite

The stage is fitted with 70 IO Industries Volucams. Of these, 39 were RGB cameras, which read and record the colour required for the .png texture map, and 31 were infra-red cameras, which record depth and position in space for creating the mesh. Avatar Dimension captured video in both 2K and 4K. The performers were globally lit, so that later in post, the VFX teams could relight them according to the scene.

From Raw Data to CG Characters

Some 700 terabytes of raw data was captured. Once selects were made, Dimension’s technical art team processed and delivered a total of 510 minutes of volumetric content over 8 weeks. Using the Microsoft Mixed Reality Capture solver, the 2D content captured on set was processed into a 3D model using proprietary Microsoft software. Props were tracked using an Optitrack motion capture system. The 3D assets were then put through a process within Houdini enabling the team to deliver them with motion vectors, a necessary task to help embed the assets within a VFX scene destined for a 2D output.

Throughout the film, the main crowd scenes handled by both ReDefine and vendor Zero VFX used volumetric capture. Dimension’s data was first shared directly with Zero VFX, who passed the processed files on to ReDefine at a later date.

Andrew has previous experience of working with volumetric characters to produce crowds from his work on ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. “The planning for volumetric projects like this is crucial,” he said. “The benefit of the technique is the naturalism of the performances, and completeness – as well as the actor’s motion, facial expression, hair, cloth motion and genuine human variation are all captured at once, as they exist in real life. To be feasible, animation in such situations must rely on a certain amount of re-purposed motion. It would be impossible to create a large group of CG individuals to look as fresh and original within a reasonable timeframe.

“However, during those performances, you have to make sure you’re capturing everything you might need on camera during the capture shoot – all possible poses and moves, types of people, costumes and so on, which is why planning is so important.”

World Tour

Once the models were in place, ReDefine were called on to build out the concert venues, scenes and sequences. These were Paul’s vision based on communications with the client, passed first to Dimension for volumetric capture and element processing, and then to ReDefine. Armed with the motion library, now populated with animated models, the team created highly customised crowds and spaces that tell Whitney Houston’s performance story, venue by venue, location by location.

Andrew said, “Our most challenging sequence was a long montage in which the audience sees Whitney on her 'My Love is Your Love World Tour', performing in one city after another. One minute she’s in London, then Paris, Stockholm and so on. Our team was responsible for building the venues, usually stadiums, and then filling each one with a crowd tuned specifically for that venue and that concert.”

“We covered the whole tour paying attention to details that made the venues contrast with each other. While the production wanted us to maintain the same energy within the sequence overall, they also wanted to see an obvious visual change at each tour stop, for example, an indoor show followed by an outdoor event.”

Building Venues

To find those differences, the World Tour montage also needed a lot of research. As Andrew researched the venues, he found that since most of them are stadiums, many are very similar but others have striking looks that the artists could highlight. Looking at the shots, they worked out a process for including a range of venues and fitting them into a story that moved along in time and geography.

“We made a list of locations, plotted them out chronologically across the shots to represent the tour, and then started building. We built five venues in total, while the edit was still underway. Doing this work before editorial was locked helped to refine the sequence in some ways, depending on how readily the available information, plus the crowds, worked together.

When it came to deciding how far to take the build, the night time setting of all concerts was a considerable advantage by allowing the lighting to guide the work. Instead of detailing everywhere across the stadium, they could focus detail in the best lit areas. ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ had involved mainly day time sequences and had therefore been a different kind of challenge.

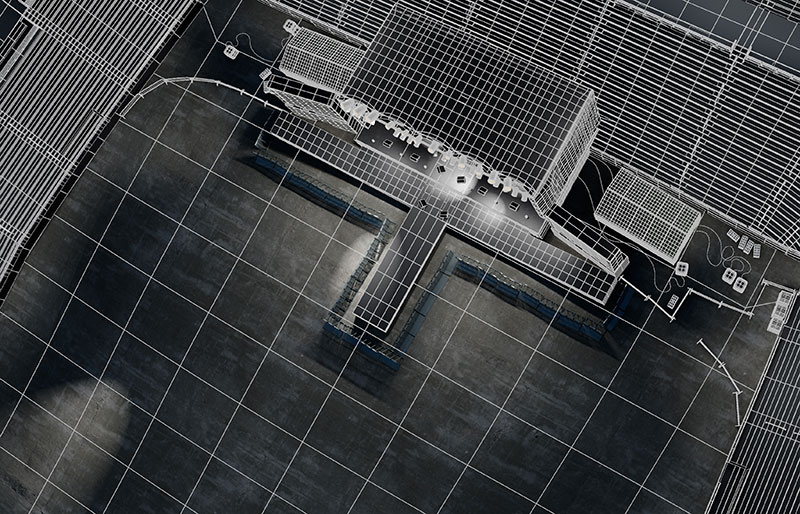

Layout

Composite

Replicating the 300 models to appear to occupy a space intended for 40,000, for example, was one side of their work – giving them the right looks and actions was another. They had to look closely at the models and motions and think about the story. Are we hearing a slow or fast song? What kinds of people are in this audience? The right kinds of moves, expressions and clapping had to be selected from the library for all of these occasions, and placed into shots with the correct timing offsets to look natural.

Many iterations were made as the team applied storytelling techniques and art direction to the sequence. For crowds in sequences not related to the Tour, they also had to consider passing time and how to reflect that through fashions and styles of behaviour. “The crowds have to react to Whitney and her contrasting performances, from shot to shot. Their looks and moves can’t be generic or recognisable. The crowd and the star were both performing with each other, and achieving believable interaction like that just needs a lot of trial and error,” said Andrew.

Crowd Control

At that point, the FX team developed a method for distributing the crowd elements into the stadium model based on points scattered across the crowd areas. Each point was associated with one crowd element – that is, one digital human – for the render. This was the distribution mechanism, but still required making decisions about what each one should be doing, and where.

“We had organised our database according to actions – for example, a person clapping with their hands above their head, clapping with hands held low, cheering this way, or that way – and each of these were labelled ‘clapping person A’ or ‘clapping person B’ or ‘cheering person’, and more. By assigning those labels to the points, we could control where certain types of action would go and determine different percentages of each action across the venue.

“Then we would check the result of the point scatter, and fine tune the result from there using percentages. If we ended up with too many clappers in an area, more cheering ones could be substituted instead, while balancing the proportions until we had the look we needed. Tempo, actions and gestures, standing/sitting/dancing – all of these needed to balance. It was important to think of the crowd as one complete entity in itself and make that work, as well as the individuals, who also need to look believable and compelling.”

Despite the bespoke nature of some aspects of this work, the team devised some time saving processes. For instance, they were able to create a ‘base crowd’ at the beginning of the project. Once they had one crowd looking very good and believable, it could then be used as an asset to start with for almost every concert after that, tweaking the percentages of the various motions and the look. Having that saved a lot of time.

Layout

Final composite

Light, Layout and the Visual Story

Among other advantages they had was the high resolution of the volumetric assets, which meant they held up to close scrutiny. The night time setting also created opportunities for visually interesting moments with spotlights moving over the crowd, or flashing stage lights on faces.

Andrew said, “As mentioned, the first questions to answer to start the crowd design process at each venue were, where should our crowd be? Where should the cameras be? The production shot a group of extras against green screen as the foreground crowd, about two to three people deep. Everything beyond that was our CG crowd. Keeping everything close to the stage limited our options, while continuing too far back gave us almost no lighting from the stage, but signalled an opportunity for dramatic lighting.

“So we would go through a layout process, placing CG cameras inside our stadium asset to show the production possible angles. As well as looking interesting, the shots had to cut in well with the rest of the edit. Collaboration was key and could help us use the crowd for visual storytelling, use light beams with a specific purpose, and create transitions to a new location.”

A Valuable Skill

ReDefine’s crowd work took 15 weeks to complete, involving over 300 artists spanning ReDefine’s facilities in Canada, London, Sophia, Mumbai and Pune. Andrew believes that the ability to use volumetric characters to good effect is a valuable skill for the team. It’s not an easy option, and won’t be the answer in every situation, however, by making that initial investment in time and creativity, it takes the team further, faster. “Your version 1 of your crowd sequence is going to be much closer to the final than the first version using any other crowd technique. The realism is already there in the characters themselves, built-in,” he said.

“But be aware that the volumetric pipeline yields a huge amount of data. Terabytes of texture and motion data were coming in from Dimension, and that had to be managed and stored. Make sure to plan for this part of the project. Each model is extremely detailed and comprehensive, 360° around it. That fact, multiplied by 40,000 people, made renders arduous.”

Therefore, the need to submit review frames to the production to get sign off for the big crowd shots was another challenge. “We utilised Clarisse, the program we used to light the shots, within our pipeline so that the FX team would only be passing over the scattered distribution points over to lighting,” Andrew said.

“Each point from FX had its attribute label that referenced one of the library elements, plus the time offset to that element. This information could be read by Clarisse and rebuilt. That way we could avoid passing large crowd caches around or large quantities of data between one department and another. Working this way significantly sped up the entire process, since FX could be passed to lighting in a matter of minutes rather than hours, leaving more time for iterations on the crowd performance and shot design.”

De-aging

A further part of ReDefine’s work on this film was de-aging the face of the actress playing Whitney Houston, Naomi Ackie. “Fortunately, the actress was already quite young looking. Also, she had to take her role from age 19 through to the mid-30s, so the job was not drastic. It was more about finding a balanced look. We focussed on wrinkles around the eyes, and lines in the cheeks. Because people’s faces grow leaner as they age, removing the lines from her dimples immediately made the cheeks look rounder and younger.

“None of our approach involved CG modelling. We could keep all alterations to the 300 or so shots within a 2D threshold, which is quicker and less costly. We used a type of non-proprietary, selective blur filter capable of removing certain details but keeping form and shape. In this case we were extracting the crease detail and either removing it or altering it, but always leaving intact the pore detail and other factors that made her face look like real skin. Facial tracking increased our efficiency but deformation of the face during expressive talking and performing meant we still needed to do a certain amount of tweaking shot by shot.” redefine.co