MPC’s VFX Supervisor Olaf Wendt talks about working with Iñárritu on the surreal and unexpectedly beautiful visualisations his team created for the Oscar-nominated film ‘Bardo’.

MPC worked with Director Alejandro Iñárritu on his Oscar-nominated movie ‘Bardo’ that brings to the screen the dreams, memories and scenes from Mexico’s history, held in the head of his protagonist Silverio, in a series of surreal and unexpectedly beautiful visualisations. The team worked on over 480 shots for the project.

Iñárritu’s film is about a Mexican journalist and documentary maker, Silverio, who lives in Los Angeles with his family. The story visualises his wide-ranging thoughts and dreams, which play out in a surreal manner due to the fact that he has just suffered from a stroke and is lying in hospital in a coma.

Those thoughts are also influenced by the conversations, music and TV programs of his wife, son and daughter who are visiting him in his hospital room. Digital Media World spoke to VFX Supervisor Olaf Wendt from MPC about the project. “Alejandro Iñárritu set out to create an immersive, dreamlike world for ‘Bardo’,” Olaf said. “I felt that he wanted to create a total experience for the audience, of which visual effects form an integral part.”

MPC’s work began in pre-production and planning some two years before delivery, when Guillaume Rocheron started as VFX supervisor. Olaf came on to work on parts of the shoot, and then carried on in that role into post.

“I went down to Mexico City to shoot the train sequences on a giant LED volume together with production VFX Supervisor Charlie Iturriaga, as well as our ‘Eclipse’ sequence – a time-lapse shot set in the centre of the city that is pivotal to the story. I also shot with Alejandro in Los Angeles for the exteriors.”

The movie was shot with a very large frame camera, the Alexa 65, for which Alejandro and the cinematographer Darius Khondji chose custom wide angle lenses – a 17mm and a 21mm. That camera and lens combination resulted in an extremely wide, immersive field of view with relatively deep focus.

“The custom lenses came off the bench just in time for the shoot, with a raw aluminium finish,” Olaf said. “The frame shows everything, clearly and mostly in focus – no blurry backgrounds in this picture. Most of the shots stretch to more than 1,000 frames. As Alejandro would say – since the audience would be looking at everything for a very long time, it would better to get everything perfect.”

Desert Flight

Early in the story we see the shadow of someone, stretching away on the harsh dry desert ground in front of the camera, with the sun behind us. The shadow begins to run ahead and we follow, noticing that the sound of footsteps and the shadow itself disappear – it has taken flight. This sequence visualises a dream-like idea, but even though we never see the person or anything but the ground, and the shadow is rough and elongated, we understand immediately what is happening, where the camera is and where the sun is.

“Alejandro shot plenty of reference footage – some of it with his own phone capturing his own shadow in the desert. He even put his lead actor on wires and filmed a take-off – which was a useful starting point for the exploration,” said Olaf.

“It’s the first shot in the movie, and the first time we see the central character, Silverio, revealed only through his shadow. This shadow had to communicate the essence of the character, but also communicate a small story arc – a progression from first attempts at take-off and flying towards a more confident, free flight. We animated a pretty detailed CG version of Silverio running across the desert, then taking off and flying, complete with a cloth simulation for his clothes and hair.

It’s actually quite a lot for a simple shadow to achieve, right through a 3,500 frame unbroken shot. Just running the sims over that many frames was a challenge. The performance aspect of the animation is surprisingly sensitive, requiring many iterations to capture the quality of the character and the sense of progression that Alejandro was looking for.

“We set up tests and completed storyboards ahead of the shoot, but not a full-length traditional previs. Alejandro likes to find the shot as he shoots. Once we had the plates, we carefully looked at the density and colour of the real shadows to match our CG shadow to. The drone that carried the camera left a shadow on the plate, too, which of course we painted out. But the experience gave us a useful reference for our shadow’s position.”

Giant hand of the fallen statue of Centeotl.

Remembering Mateo

Silverio and his wife Lucía have a happy life together and have two almost grown-up children, but they are haunted by the death of their first son Mateo, only one day after he was born. They keep Mateo's ashes and feel unable to completely let go of him. In the film, we encounter Mateo at three slightly different stages of development – newborn, at 3 months and at 6months. The baby had to seem completely real so that viewers do not focus on his looks but instead share the emotions of his parents.

Olaf said, “Alejandro shot reference passes of a couple of real babies. We based the facial features largely on one of them. It would have been great to use real footage, but you can’t really direct a baby’s performance – especially a newborn’s – nor can you easily shoot the same baby at three different ages. Furthermore, not only did Alejandro want the audience to be able to recognise him as the same character at each of the three stages of life, but he was also after a particular performance. All of this necessitated a CG approach.”

Skin and Head

First, we see him at the hospital just moments after he is born, when each minutiae of his look made a huge difference. “You can be 95% of the way there and it still feels way off,” said Olaf. “The last 5% can take as much time as the first 95%. You only can judge what is missing once everything you’ve set out to do comes together. It’s not a simple, tested recipe. Subtleties in skin/fat tissue simulation can change the impact of animation nuances, changes in the lookdev can emphasize or de-emphasize movement, and you’re always dealing with hugely long shots – thousands of frames.”

The right amount of suppleness and translucency in the skin proved to be a fine balance. In the hospital where the doctors’ hands carry the baby, that sense of weight and contact became a further challenge. “In the plate we used, the actors handled a stiff puppet that we painted out. But our CG baby moves, so in some cases we had to animate the doctor’s fingers and hand position to maintain believable contact with our CG baby.”

A newborn baby usually looks quite different from a 6 month old child – with a much more squashed head shape, for instance. The initial design skewed closer to this, but then we integrated more of the facial features and head shape of the 3 month and 6 month old. However, that third iteration required an interesting scaling challenge – he had to fit into his mother’s hands.

Farewell

The family gathers on the beach at the water’s edge to finally scatter Mateo’s ashes in the sea. But when his mother opens the urn, instead of ashes we see the tiny baby, whom she picks up lovingly and places in the water to swim away. Preventing him from looking like a doll required skillful use of the photography, though in fact, Alejandro shot the plate with a small doll to give the team the correct size and rough placement in the hands and serve as a good lighting reference.

Olaf said, “The doll had to be painted out requiring some tricky reconstruction of the obscured fingers, and subtle integration with the right shadows cast by the fingers. We had to adjust the skin shading to feel correct at this size and in the bright sunlight. The baby’s performance had to convey a mixture of calm and reaction to the strong sunlight, and the sense of weight of the baby in the hands. It’s very subtle stuff – you really only see the true effect of any animation changes once you simulate the skin tissue and render it. Everything interacts, creating quite a challenge for compositing on a 3,500 frame shot.

“For the swim, we amassed plenty of references of babies in water – though usually they are too active. We hit the swimming action reasonably quickly, the crawl on the sand presented more challenges as it easily looked too frog-like and symmetrical.”

Father and Son

MPC also handled a sequence in which we see Silverio talking with his father, who is now deceased, making up for past misdemeanors. The director’s vision required building a complex hybrid character combining the adult head of Silverio with a child's body. To do this, Alejandro separately shot the 50 year old actor playing Silverio and a 10 year old boy performing roughly the same actions, at matching angles.

“In some cases, we could combine the live-action elements of Silverio’s head and the boy’s body using complex respeeds and 2D warps,” said Olaf. “Alejandro wanted this sequence to feel a little comical but completely believable, so the connection between head and body had to feel solid and seamless. We experimented with an even larger head in relation to the body for comical effect, but found that it lent a too top-heavy feel to the character.

“As all the subtle head movements had to be reflected in the movement of the body, in quite a few instances we had to replace the body with a CG animated version – for example when Silverio laughs or turns his body. Shots with large body movements – walking, turning, drinking from the cocktail glass – all presented the biggest challenges. In some cases we had to re-project Silverio’s head onto a CG animated head, often replacing the hair to match the walking and turning motion, but the frequent body contact between Silverio and his father when they embrace could mostly be achieved by piecing together live action elements.”

To handle the different points-of-view throughout the sequence they grouped the work into the main four or five angles. It was mandatory to create a consistent feeling of size, which for some angles meant subtly tweaking the relationships between body and head and the father owing to the extreme wide field of view.

Mexico City

From dealing with tiny details of digital human modelling and animation, MPC shifted gears to a vast surreal environment, a re-creation of the historical centre of Mexico City with a giant dead god and a pyramid of dead bodies. Although it takes place on a dark, gloomy morning before dawn, the setting of this sequence soon becomes clear – we are in the Zocalo [central plaza or square] of Mexico City, a huge open space with distinctive, well-known features.

Fallen Aztec god Centeotl.

“Part of the sequence, the first five or so shots, were shot on location at the Zocalo itself, and to those shots we added the giant statue of the fallen Aztec god Centeotl – a major CG build. But the rest of the sequence that unfolds as Silverio climbs the pyramid of bodies was shot on a stage. We had to build a CG version of the square for those shots based a Lidar scan of the location.

“Since Alejandro knew the location well, he was keen to make our recreation match reality as far as possible, down to the positioning of lamp posts. The location photography of course served as excellent reference for the look, while matching the lighting and feel between the two parts of the sequence – on location and in-studio – required blending subtle atmospheric layers. The studio lighting was a bit different from the location plates so we spent a lot of time massaging the lighting and look to bring all the shots into the same world.”

As Silverio climbs, the pyramid continues to extend up, up, up and he seems unable to reach the top. Meanwhile, all the bodies on the pyramid look quite dead at first, but shortly they begin to come to life. “The studio photography used a partial practical pyramid with hundreds of extras. In many shots we had to extend this pyramid, doubling its size using plate elements as well as ‘dead’ digidoubles, but the living people were luckily all live action and in-camera.”

Multi-layered Time-lapse

When Silverio takes a stroll through the streets of central Mexico City, the story takes another surreal turn. Passersby fall to the ground, dead, and the sun passes rapidly overhead toward nightfall, which MPC achieved with a multi-layered time-lapse – that is, combining a timelapse background plate shot on location in Mexico City with studio elements of Silverio stepping over a team of ‘dead’ extras on the floor.

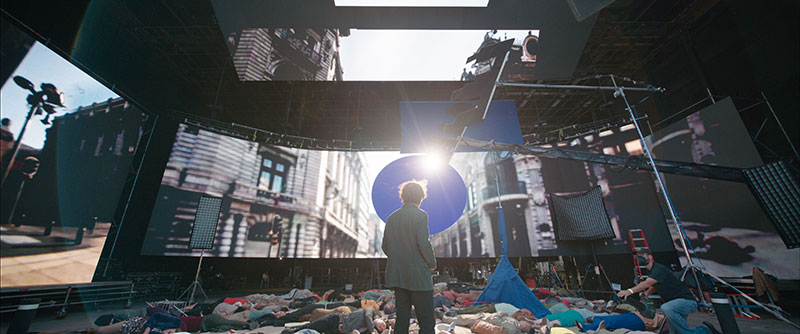

Above: Silverio in the LED volume

“The challenge here was to shoot the live action elements of Silverio and the extras with lighting that matched the rapidly setting sun in the background plate. An LED volume provided the correct fill light and ambient twilight, but would be unable to simulate hard sunlight. So we mounted the most powerful remote-controlled pan-and-tilt spotlight we could find on the end of a technocrane and carefully synched its movements to the setting sun in the background plate – a big shout out to the grip crew who handled this challenge beautifully.

“This spotlight illuminated Silverio and a few of the extras right next to him, but had too small a reach to illuminate all the extras on the floor. Some carefully rigged gobos cast shadows on Silverio just at the right moment when the ‘sun’ is obscured by a static CG cloud – with an effect much like a solar eclipse – that we added to the background plate. We shot additional lighting passes of the other extras, and then extended them using CG digidoubles into the distance. All in all, it was quite a challenging shot to pull off.”

Complex Composites

As well as this special time-lapse shot, MPC worked on many other elaborate composites that blended multiple takes of action and characters into long continuous shots. These contribute much to the surreal quality of the movie. Olaf said, “We didn’t use motion control but relied on reasonably close camera positions in the plates that were mostly shot on Steadicam. When pulling the shots together, almost all of the stitches required partial CG reconstructions and re-projections to precisely match camera positions from one side of the stitch to the other.”

However, other such shots needed a completely original approach. A good example is the ‘mirror’ shot of Silverio meeting a reflection of himself in the desert. His reflection walks off while Silverio remains standing, so the shot is pieced together from a number of plate elements with hidden hand-overs. The ground and distance had to be carefully reconstructed to remove the camera crew.

“The original version of the ‘desert stitch’ ran to 11,000 frames using six separate plates – a monster that we broke into a number of sections. As a result, it’s quite a bit shorter in the final version of the film,” said Olaf.

“There was no standard approach, as such. Lighting changes – especially lights shining in different directions – between the different plates had us looking for somewhat different solutions each time. The position of the sun, for instance, is handled with a bit of sleight-of-hand as it jumps a couple of times.

“Each section required extensive clean-up as well to remove footprints, broken terrain, tracks and distant structures. We built a CG desert floor that could be patched into places that required it. Meanwhile, fidelity to the photographed desert was paramount. Alejandro loved the subtle changes in texture and colour of the desert in the plates, which we had to preserve. The giant hand that appears at the end was represented with a rough mock-up in the plates – we replaced it with a CG version that matched the style of the fallen statue of Centeotl in the Zocalo sequence.”

LED Volume Work – Train Sequences

MPC’s artists also delivered LED volume work for several train sequences. Instead of replacing green screen in post, the set for the train interior had been built on a sound stage surrounded by LED screens displaying video of the story environment. Alejandro had shot plates on a real Metro line in Los Angeles using fisheye lenses in order to achieve the right coverage for the extremely wide-angle main unit photography.

Olaf and Charlie Iturriaga were on set for the LED volume shoot in Mexico City, where they had to calibrate and undistort those LA plates and then redistort them to match the curvature of the arced screens of the LED volume, and then line them up to the camera. Nevertheless, many of the shots still required perspective correction in post. Perspective and coverage fixes, and sometimes colour tweaks, in post are all part of LED volume work, and in some shots they swapped backgrounds.

“The light cast from the LED screens onto the train set gives the sequences much of their realism and, for me, that’s the most important advantage of LED volume work – you can always fix issues in the backgrounds, but it’s very hard to fix lighting on the foreground elements,” said Olaf.

A Time-honoured Technique

“I see LED volumes as an extension of the time-honoured technique of rearscreen projection that has been used for probably 100 years. Naturally, LED screens can make the process more flexible, and LED screens generally have higher light output than a rear projection screen. For many applications, trains and cars for example, the approach is quite similar in principle to traditional rearscreen. I remember I did a few quite large scale train sequences in 2006 for a film called ‘Derailed’, all in-camera using a line-up of digital projectors – so this procedure feels quite familiar to me.

“The challenges are always having the right plate material, projecting it in the right colour space and perspective, achieving the right illumination and preserving black levels as much as possible, and avoiding moire patterns due to the LED spacing – not so much of an issue on this show thanks to the wide-angle lenses.”

Many of those train shots also feature CG axolotl, which are rare, aquatic salamander creatures native to Mexico that we see swimming around the flooded train. They had some live axolotl on set but unfortunately, according to Olaf, they don’t take direction very well! He said, “Alejandro was after a particular choreography for the axolotl, especially when Silverio chases them down the water-logged carriage. The axolotl have a very specific, almost velvety look underwater that took some care to replicate.” www.mpcvfx.com