VFX Supervisor Paul Santagada talks about the 3D environmental and FX work at FuseFX to support the hand-built sets and stop-motion animated performances in ‘Wendell and Wild’.

The team at FuseFX is proud to have contributed 3D environment and FX work supporting Henry Selick and Jordan Peele’s stop-motion animated movie ‘Wendell and Wild’, a Monkeypaw Productions and Netflix Animation production.

Discussions that started in 2021 between FuseFX’s Vancouver studio and the Netflix Animation team led to Fuse being awarded a substantial portion of the movie’s VFX work, which was divided between their Los Angeles and Vancouver teams. VFX Supervisor Paul Santagada in LA talked about their work with Digital Media World.

“Although I hadn’t had any direct experience in stop motion animation ahead of this project, especially not at feature film level, I jumped at the chance to be a part of it. It was an exciting, unusual opportunity, and we became a very committed group here,” Paul said.

Jordan Peele and Henry Selick are the production’s co-writers and creators. Selick, known for earlier stop-motion features ‘Coraline’ and ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’, also directed the production and animation, and first contacted Peele about his story ideas as long ago as 2015, meaning that the whole project – story, development and production – took some seven years to complete.

Its extremely complex story concerns two demon brothers called Wendell and Wild who strike a deal with Kat, a 13-year-old punk rocker, to bring her dead parents back to life if she will help them reach the Land of the Living. The adventure that unwinds from there, populated by a cast of beautiful puppet characters and intricate sets, is what ‘Wendell and Wild’ is all about.

An Art-Directed World

FuseFX worked on the project from mid-January to July 2022. The initial work was identifying the sets and set pieces that would benefit from CG augmentation. Background art is an issue for stop motion animation because only so much of a world can be addressed on a stop-motion animation table. While it may be possible to physically build sets that appear to extend into the distance, actually doing that can limit the scope of a production and in any case, the animators really want to be devoting their energy to the characters and set pieces immediately around them.

Paul noted that their work was to continue, not replace, the physical sets and props. Doing this job properly meant truly understanding the film’s art direction. “Our CG Supervisor Efram Potelle studied many photos and videos illustrating how the set detail was styled and put together – from rocks, vegetation and pathways to the sprinkling of snow,” Paul said.

“The puppets in our shots were never performing against a blank green screen. They were always working on a carefully dressed animation table with some green inserted behind the props and puppets, and that was where we would fill in the ‘blanks’ according both to references and to story requirements. Every shot was a bit different.”

On the Sets

Fuse LA would handle the Rust Cemetery sets, involving a number of night-time sequences and dialogue sequences in which a number of characters are talking, requiring the camera to shift back and forth between them. Each camera move needed a complete, consistent section of environment behind it.

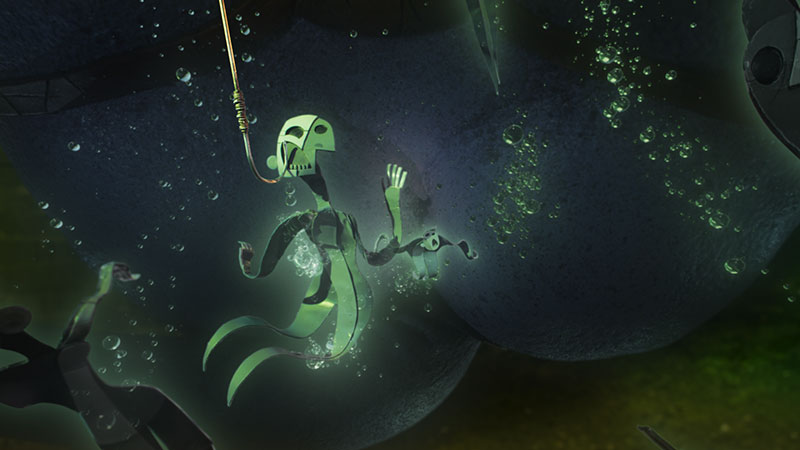

Fuse in Vancouver worked on the underground world of Belzer, a character so large that he eventually becomes an environmental feature. Essentially a well, his environment is a bullet-shaped hot tub chamber, full of liquid, that he shares with his bizarre fairground. It was fully contained and more limited than the cemetery but highly detailed and textured.

As FuseFX and the production planned out the two studios’ work, it amazed Paul that this incredibly lengthy project could need such precise scheduling. But he soon realised that every step involved a huge amount of detail that could easily have fallen into chaos.

“Production took place at a studio in Portland, Oregon, that was constantly busy and crowded. Though it wasn’t possible for our team to visit the sets, the production’s internal team supplied us with hard drives filled with excellent reference that helped us create our builds to match the sets as authentically and precisely as possible.

“This material included scans, often LIDARs, of the animation tables and set pieces at full scale, which varied in density and quality but were more than enough to recreate the complete cemetery location. Using this digital version as a base, we could accurately build our extended environment. We had photography, libraries of asset reference like turntables and textures, spreadsheets of measurements, plus lens data and camera information.”

Continuity

Conceptually, the Rust Cemetery was a bowl shaped environment up on a hill above the town, populated by a mausoleum, a cemetery wall, rock features and an overlook at the back looking down toward the town. To build that entire environment at 1:6 puppet scale would have been a massive fabrication. Therefore, the Netflix Animation team had built separate animation tables for sections of it as needed for the sequences taking place there.

FuseFX built 3D portions for the environments to support those sets. Continuity was key, ensuring that all cemetery shots would be recognisable as part of the same bigger location. The look would need to change from sequence to sequence as well, but always be immediately identifiable as the cemetery environment.

Paul said, “We were basically looking after any in-frame content 20ft or more away from camera, which often left plenty of room for storytelling between physical set elements. While we were busy with light fall-off from foreground to background, level of detail and so on, any stylistic decisions could quickly be resolved since we had so much 2D and 3D reference material. Also, we were in constant communication with the DP Peter Sorg, Matte Painting Supervisor Heather Abels and Art Director Tom Proost. We really became part of the team.”

Suns, Moons and Skies

A major and very interesting feature that the animators really could not build on set were the skies, which often served as an important story point. Fuse received details about the requirements via beautiful mood boards showing how the skies should vary from scene to scene, and the circumstances of each one. Desired colours, opacity and amount of cloud cover were represented in paintings of small segments of sky in which a full moon usually featured.

“The full moon was critical to the story but made scenes with cross cutting – like conversations between chars – more complex to light. We needed to rake the keylight across the faces accurately,” Paul said. “Regardless of who was talking to camera at any moment, the moon always had to be present and accounted for, even if it were off-camera. The rest of the sky that was in-camera, had to coordinate with that moon section.”

Camera effects, lighting and scale had to be adjusted in different ways, at different times. The real world size of lighting fixtures compared to the puppet world had to be taken into account. Although Fuse has experience building 3D light rigs to match lamps, reflectors and other lighting gear, placing the same gear on 1:6 scale sets made it feel huge. This makes the reflectors or the cone of light from lamps behave differently than normal, calling for changes to their usual light rigs.

“Also consider that light rays from the sun or moon in our world are essentially parallel by the time they each earth, but in the studio, the lamp for the ‘sun’ or ‘moon’ would actually be producing angled light. So, for interiors or exteriors, when building the light rigs we had to consider which reality we would choose and how far we would take it in each case,” Paul noted.

A New Perspective

This challenge was similar to the choices they needed to make regarding perspective. For example, depending on the requirements of the shot, the cemetery set on the animation table would be dressed with rocks and other features that were precisely sized and positioned to suit the frame, action and angle in order to give the correct illusion of perspective.

“As we designed our digital work, our job was to preserve that illusion in whatever way we could. So it wasn’t strictly possible to build one true 3D model for all scenarios. We would have to decide – should we match the physical build that would be slightly distorted to impose real-world perspective on a tiny set, or carry on as if the set were built normally around the action? The decision had to made shot by shot, going in and pushing vertices around to match the physical set, squashing assets, frequently rebuilding the 3D.”

Depth of field was a creative filmmaking device that Fuse helped the production with. In live action cinematography, changing the level of detail in a scene with depth of field is a way to guide viewers’ attention and express something about the character or the story. But shooting miniatures requires closing down the camera’s aperture, which creates an infinite depth of field and means that reducing level of detail has to be done manually by removing objects from the set. Applying depth of field as a camera effect in post made that manual work less necessary.

FuseFX also created certain FX work that couldn’t be produced practically – fluids and bubbles around Belzer’s chamber and characters vomiting, for instance. The animation team went out of their way to show Fuse exactly what they were aiming for in the look of the effects. “For a scene when Father Bests revives and spews up quantities of pond water, the animator constructed a model of this with acrylic tubes, spinning in their arc from the character, embellished with small splash animations. We all knew then what was expected.

Breath of Life

“The breath system was an interesting effect we developed for the puppets in sequences when the action moved outdoors on cold nights. One of our FX artists built a system creating animated, puffy procedural breath that gave the puppets a tremendous feeling of life. The animators supplied reference video of themselves, going outside on cold nights in Portland to record each other talking against a black wall.

“Because the characters move through frame quite quickly, turning first one way and then another, we had a procedural particle system that allowed adjusting the emitters to push out the breath in a precise direction. Seeing them performing on screen for the first time was amazing but actually seeing them breathe air makes them feel so alive.”

Shot assembly was an important stage because so many sequences were shot in a huge number of passes with a motion control camera. The Vancouver team had some shots with up to 60 passes. For an action packed chase sequence down a mountain, some characters had a pass to themselves. Then there was a pass for lightning, several for falling debris, fringes on clothes, tails or arms flung wide. Shooting in passes was also a way of managing small sets with limited space for the animators to work in. Then finally, all of them had to be assembled into the final shots.

Stop-Motion Reality

Realism was needed as an element of all their work, but it was a crafted reality, always in terms of the movie and its world. Everything Fuse did radiated off of the character work the animators were doing – it was more a matter of supporting and not adjusting or changing anything. It sounds straightforward but prompted some unusual kinds of problem-solving.

Paul said, “Stop-motion anim has characteristics in common with the in-camera VFX that artists are developing now for virtual production. So much of a stop-motion production happens before post. Much of the editing and decision-making is done on-the-fly, directly from the storyboards, to save costs and time.

“You have a clear sense of what will be needed in the final version than you do in live action, where the DP may shoot to cover later decisions. Bound to the story you are telling, you have a specific focus with a closed-system pool of information to work from, and all your materials are there from the sets for you refer to and work with.” fusefx.com