The effects team at Iloura built a cavernous underground world for 'Sanctum', Producer Andrew Wight's story of danger and adventure. VFX Supervisors David Booth and Peter Webb with editor Ben Joss talk about their own adventures taking the movie, shot in stereo 3D, through post production.

|

|

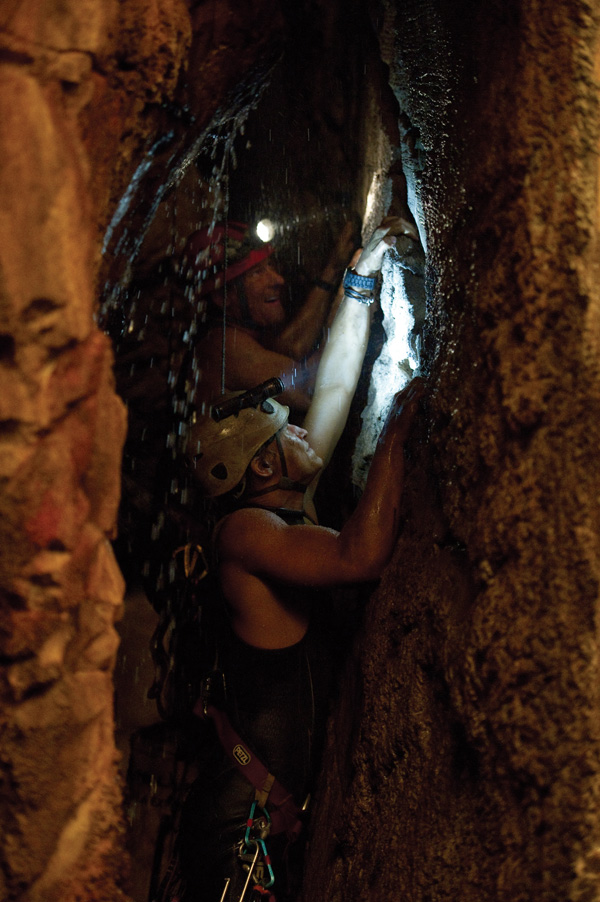

The film was shot on the Gold Coast in Queensland until March 2010, when the footage was brought back to Melbourne for post. Editor Mark Warner and the editorial team's first step was two weeks of assembly for the director to look at, from which the producer's edit was cut. During assembly, First Assistant Editor Ben Joss was also working with the director to cut together the VFX sequences. Cave Research VFX shots were needed from the beginning of the film, with a helicopter flight over the jungle forest, the aerial reveal of the cave's doline – the Esa-ala Caves' entrance, an enormous sink hole surrounded by forest - the hole itself and the characters' entry into it, and continued throughout the film, focussed mainly on extending the foreground sets, shot against green screen, with massive, detailed CG cave interiors. Although fairly extensive practical sets had been built at the filming locations on the Gold Coast, a number of the underground caverns needed to be as large as football stadiums and reveal fantastic structural designs that would have proven monumental to construct. As the production's on-set VFX Supervisor, David was responsible for gathering all information the FX team at Iloura would need to create these extensions from the ground up. He and Producer Andrew Wight took a trip out to South Australia where they could study a real doline set in limestone although, at 3m across, it was much smaller than the Esa-ala Caves represented in the film. Even so, on their trip, David photographed vegetation, light angles and effects in and around the doline. He also collected photo references of rock formations and textures, which the team could use to fabricate their own rock textures and surfaces to project onto their 3D cave geometry. Working On Set David explained that when shooting scenes in stereo involving green screen replacement, it was important to keep the interocular distance locked during camera moves, to avoid having to repeatedly adjust the convergence point later in post. To begin work on such shots, the team's tracker would make sure the live action left and right eye images matched properly before the artists inserted the background extension in the right eye shot, which they used as their master. When everything was complete the same work was applied to the left eye. Because setting the convergence was critical to getting these shots to work, from the foreground straight through to the CG background, keeping the I/O locked during the shoot was helpful. Terrain Challenges David said, "One of the most challenging CG sequences illustrates what the director had underestimated – to tell this story, the audience had to see the environments in detail and comprehend their scope and size and consequently, many shots from various angles had to be created throughout the film. This scene was at the vast cave entrance, as the characters abseil and parachute down to the interior below. A ledge was built for the actors to jump from, over a 40ft deep space. The VFX team had to build the cave environment, the parachute, the parachutist, birds, falling water and light shining through it – all in CG, down to the bottom." |

|

|

Image Correction Also the headlamps the actors were wearing tended to dominate shots in which the convergence had been changed, and David would have to reduce the detail in the lamps and adjust the shot. Furthermore, while they read reasonably well in the live action footage, they weren't so successful against green screen and had to be removed and replaced with CG beams, ensuring they were shining in the correct direction to work stereoscopically as well. Alignment and Colour The original footage had to be prepared before it went into their VFX pipeline, checking for alignment and colour disparity problems. The success of all of their effects work would depend on correct stereo alignment and positioning of the convergence point relative to the interocular distance. The team helped David Booth with some of the image correction work, using Nuke with the OCULA plug-in. The right and left images of shots requiring set extensions and compositing in CG elements, in particular, had to be tracked before the team started work. Aerial Views But in fact, they ended up 'cheating' on the size of the hole in some shots in order to produce the necessary dramatic effect. In some instances they had to make it twice the actual size than in others - after all, it was going to be the focus of the entire story. Nuke with OCULA, plus a few of Iloura's own techniques, helped blend the CG into the shots while making sure the stereoscopy was consistent. Sense of Scale Working with light, how it fell on objects and calculating the light fall-off and pinpointing distance when the camera faced out into the dark reaches of the set extensions was another way of conveying their size. Up to a point, this could be based on how light from the actors' headlamps behaved in the built sets. Atmospherics such as drifting rain and water helped to occupy the huge spaces and catch stray shafts of light. Creating such massive set extensions as the caverns tends to make the usual use of HDR images of the set for lighting inadequate. However, given the story's underground location, the absence of a natural light source would have meant the only available light would have come from the divers' helmets, requiring the artists to creatively introduce enough additional light to make a worthwhile viewing experience while maintaining an authentic feeling. "Our designs for the sets were just a start point," said Peter. "From there, working with the lighting and the stereo became a creative process." All of these elements were calculated into their complete light simulation, and although everything started with real-world calculations, once each sequence was in the review theatre, it had to be assessed for dramatic impact, storytelling and the director's vision. Sometimes the environments needed to be brighter, darker, or appear closer or further from the camera. Reference To create the rock surfaces for their set extensions, they used the hundreds of high-res reference stills David Booth had taken on set and on the research trip he and Andrew had made to South Australia. Helping to define the interior structures, in the absence of a real location to scan, were Andrew Wight's photos and reference material gathered during his caving trips, which gave them a real-life start point for the looks of the environments and lighting. But each cavern had to have its own looks and personality – St Jude's Cathedral, the Belfrey where Ben and Frank discover a Japanese tank, the huge desert-like set the team called the 'Sunless Sahara' due to the sand dunes covering its floor – and had to be referenced separately. The team also did some of their own research. Nevertheless, no single source was able to give them exactly what they wanted or needed for each of the caverns and so the caves seen in the film are created with digital matte paintings projected over CG modelled terrain. |

|

|

|||

|

Setting the Stage Sunless Sahara A number of CG doubles were needed to replace characters at certain moments. For example, although the actor playing Carl did leap out into the space over the doline, requiring wire removal, from that point a digital double replaced him in a shot showing him descending under a CG parachute. Some body doubles were also used in underground caving sequences, especially looking down narrow shafts at climbers with their headlamps switched on and some of the divers underwater in scuba gear. Fortunately, none of these were at close range, so facial detail wasn't required, and performances were fairly generic and didn't need motion capture. The artists started with standard human models and then worked with photos of the cast to customise their proportions and colouring. Props and Creatures A few environments nearer the surface needed the addition of CG creatures. CG bats were added to the Belfrey set, for example, and swallows flew through the doline catching insects. These animals helped complete the authenticity of the upper cave system environments. Flocking algorithms helped them distribute large populations of birds or bats, combined with some hand animated individuals to add interest and variety as they took off or landed. "Our cave swallow references included their small mud nests, which we built clinging to the walls and rocks. These creatures, I think, really help the shots to work and feel alive for the viewer." Underwater World Digital Roller Coaster The stereo aspect of the project combined with the fact that this was their first project creating and working with assets and CG environments at such a large scale and with such unusual, even fantastical designs, made this project a significant challenge for the facility. Peter estimates he spent at least five to six months researching before any shots arrived at Iloura, followed by six to seven months of actual production. The knowledge and experience they have gained seems to be paying off, and they are now working on another stereo project. |

|||

|

|||

|

Stereo Editing To make the monitoring work, Ben had to get the left and right eye into their Avid system. The footage was digitized straight off the HDCAM SR deck onto their Avid system as HdDNX36 MXF media, one eye at a time. The recorder put both images onto the same HDCAM SR tape into separate streams, a format Sony calls 422x2. They edited the film first on the right eye, and assistants conformed the left eye to match it afterwards. Because the left eye had been digitized already, they didn't need to return to the tapes, but simply treated it as separate media. Phasing As the editors worked on the film through the various passes, they sent the EDL to the Technical Director at Digital Pictures, Nic Smith, who would update the timeline and use it to conform the footage for the DI on their Lustre suite. From the Lustre, the VFX team extracted the clips they needed to work on as DPX files in separate left and right passes. Digital Pictures soon discovered a phasing problem between the two versions, in which the time code sometimes varied between Iloura's version and the editor's EDL. In a number of cases, this appeared to have been caused by not giving the deck enough pre-roll time when digitizing the footage into the Avid, although some other shots with plenty of pre-roll showed the same problem. Nevertheless, the camera crew aimed to allow at least 5 seconds pre-roll before the action but in reality, action on set often occurs right after the camera rolls, so this could be difficult to manage. QuickTime Check Although the Avid does have a stereoscopic menu, they didn't actually use any of its features. "For example, there's a setting for the type of stereo footage being dealt with – side by side, up and down, interlaced, anaglyph and so on, plus your preferred viewing format," Ben explained. "But while stereo footage involves two discrete images, the Avid wants these to have been combined in some format, before it interprets it for viewing. On the client monitor, it will always show both left and right images but on the internal monitor you can select different displays. Also, if you want to use correction tools to adjust conversion or blow up a shot, none of the available effects tools work. You would need to have both images there and treat them separately. Discrete Images |

|||

|

|||

| STEREOSCOPIC RIGS Both beamsplitter and side-by-side rigs, two of each, were used in the production. The two types of rigs had different advantages and shortcomings. The beamsplitter is larger and bulkier and produces an inverted left eye image, but it places the cameras one above the other, thus allowing an interocular distance of as small as 0 if required, making it useful for close up shots. The side by side rigs are more compact and both left and right eye images are oriented correctly, but the I/O distance is larger and less controllable. Typical interocular distances during production were about 2.5cm on the beamsplitter and 6.5cm for the side by side. As mentioned earlier, David developed a compact beamsplitter rig in underwater housing, employing two DSLR cameras to overcome the side by side rig's wide convergence angle that prevented close up shots underwater. David also ensured the rig would be synchronous. He successfully constructed a rig of the required size configured to hold two Nikon D3S cameras, and Nikon helped by modifying the cameras to be synchronously operated. Simon Christidis, the underwater cameraman, made the housing and controllers. The camera was quite successful and David experimented with it on some of the shots, but unfortunately they were not used in the film, mainly because the MPEG 4 image quality was considerably different to the HDCAM footage shot on the Sony CineAlta for the rest of the movie. But it worked well and when James Cameron visited the set and saw it, he was impressed by its potential for future productions. |

|||

| Words: Adriene Hurst Images: Courtesy of Iloura, Great Wight Productions and Universal Picture |

|||

|