VFX supervisors from One of Us and Framestore talk about their work on Netflix science fiction feature ‘The Midnight Sky’, creating Jupiter’s moons, spaceships, a dying Earth and holograms.

Living alone on an outpost in the Arctic, Augustine is among the last survivors on Earth, which is rapidly dying, and is terminally ill himself. He needs to contact the spaceship Aether to warn the crew of the deteriorating conditions on Earth before they return from a mission in search of habitable worlds. But to send a strong enough signal, Augustine must trek from his Arctic base through a radioactive ice storm to equipment at a weather station.

To help visualise this science fiction drama, 'The Midnight Sky', the team at One Of Us was hired to design and create effects ranging from the expansive landscapes of K-23, a habitable moon of Jupiter, and the interactive holographic experiences Aether’s crew share with their families back on Earth. Visual effects supervisor Oliver Cubbage led the artists, working alongside the production VFX supervisor Matt Kasmir and director George Clooney.

Oliver travelled with Matt to the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands to film the background plates for a dream sequence that unfolds on K-23. A volcanic island, the landscape of La Palma is beautiful but alien looking, making a suitable backdrop to build the new world from. The trip took place at the end of principal photography, and was the last sequence to be shot.

From La Palma to Iceland

Oliver said, “The design for K-23 was ever evolving. George was always adamant that it should be grounded in some sort of reality, be that real lighting from the sun on the character, real wind or real foliage nearby. The backgrounds in the early part of the sequence were largely captured in camera. With selective grading and subtle CG augmentation, they soon began to feel like they were from a different world.

“The final design in the latter part of the sequence, when the character Sully runs into a field, was based on a very open terrain, distant mountains and canyons, rivers and lakes. As she runs out, we see less and less life, simpler plants, less vibrant colours, culminating in a much more open vista, enormous and moonlike.”

In fact, the primary photography for those backgrounds came from Iceland, where the geology already looks very alien. By shifting around the colours of the vegetation in the foreground and background, they conveyed that alien quality and also connected it to the beginning of the sequence, using a palette of oranges, reds, blues and pinks.

On a set dressed with carefully designed ‘alien’ plants, the production shot the plates using a stand-in actor. Close up green screen shots were recorded in a studio with the main actor, who was pregnant and could not travel.

One of Us combined the plates with digital matte paintings and many CG elements, which required precise compositing because the environment needed to be seen at different scales. The camera starts with a close-up of Sully taking samples from a stream, then travels through a ravine, its sides covered with unearthly plants, which then opens out to a field, and beyond that a plain, mountains and the sky dominated by the parent planet.

Ecosystem

Everything about the K-23 environment had to be coherent and believable as an ecosystem, but entirely alien – the challenge was to choose which laws of nature to obey and which to break.

“We received some concepts from the client initially but the whole sequence went through several re-designs,” said Oliver. “As George’s and the studio’s ambitions and intentions for the sequence developed, we offered new ideas for how the environment might look until we hit on something that everyone felt was alien, but not too dissimilar from the rest of the film.

“As the sequence unfolded, the idea of the world continuously opening up around the character determined the way each shot evolved and the geology that was selected. The time jumps in the sequence, and the fact that it's a dream, gave us some licence to compose things shot by shot and transition quickly from one set piece to another.”

One of Us wanted to take the authenticity of what was captured on location as far as possible. For Oliver, this is the advantage of not shooting on a green screen. “The complexity and language of reality is incredibly difficult to replicate. Leaning on that real world photography was critical in making something believable. It's much easier to work on top of that as a base than it is to try and invent something from scratch,” he said.

Breaking Laws

Balancing the need to break or obey the laws of nature brought some interesting results. For example, except for the planet Jupiter, the sky overhead looks quite dark, but from our POV on the surface with Sully, the atmosphere feels bright and sunny. Taking a cue from views from the summit of Everest – a tight band of colour that quickly blends into the dark sky above – the dark sky was due to the lack of atmosphere.

“Since the rest of the film is mostly set in the darkness of space, they didn't want to steer too far from that palette. Also, the storyline dictated a constant need to connect to the planet Jupiter, which was why it appears so bright in the sky. The colours of the landscape and the blues and oranges in the sky tie into the colours you see in Jupiter, making it all feel like one world.”

When we see Sully running through the field of alien grasses, each plant moves separately as it blows in the wind. This was all done digitally in Houdini by building a setup that allowed them to play with the speed and direction of the wind and the frequency of the gusts.

The team stretched the proximity and legibility of the other moons of Jupiter, positioning them purely for compositional purposes and not scientific accuracy. Because the moons, Jupiter and the sky were the key to the story and to the overall feeling of K23, they made a conscious effort during the final re-design to let them occupy more of the frame, and to confine the vistas to a narrower portion. Strong lighting on the moons, mountains, ice shelves, as well as areas of the field also helped connect the two spaces.

Colour Connection

“The simple colour palette was crucial to connecting foreground and background, and was an ongoing exploration throughout post. We achieved the look on the earlier shots within the canyon first, before rolling it out across the whole sequence. We knew we had to remove the green parts of the plate to distinguish the planet from Earth,” said Oliver.

“By despilling the green foliage, then selectively boosting the saturation, we began to see something that felt alien but also sympathetic to the palette of the rest of the film. It needed a huge amount of fine tuning, dialling more colour into some plants than others, adding mist into areas of the shot, also selectively grading running or dripping water towards the colour blue to avoid direct comparisons with Earth.

“We were always conscious not to push the look too far. working with what was shot on location placed a natural limit on us as well, and I think these restraints helped us stay very grounded in a result that isn't too much of a stretch from what we experience here on Earth.”

Home Away From Home

The family holograms were holographic videos of the crew members’ families at home, designed to comfort the crew. They were important to the director, who wanted them to convey a specific emotional element of the story. Oliver said, “To portray the melancholy of separation, the system’s holograms were made to look imperfect – like the crumpled photograph in your wallet.

“Most of this treatment was created by hand in compositing, Once we had the look defined, it was rolled out across all the shots and then tweaked. Some shots were close up and some at a distance and the effect had to be modified accordingly. VFX is often called upon to create spectacle, so it is an exciting design challenge to find an abstract way to evoke emotion.

“The production side of these scenes was approached in different ways. For example, the scenes with the character Maya on Aether with her family in New York, we actually shot in camera – complete and simultaneously. The production built the set of the New York steps into the space ship set. We then added our digital hologram effect on top of the family members, utilising clean plates of the set to paint in behind.”

Mitchell, on the other hand, was shot on his own on the spaceship interior set for his family hologram. The background plates of the family kitchen were shot at another location and re-projected onto geometry in comp before applying their holographic effect.

Maps and Charts

One Of Us created several other pieces of holographic equipment aboard the Aether and in Augustine’s Arctic base. Augustine uses a dimensional map that takes shape and comes to life as the relief, features and clouds appear. Instead of a 3D animation, this process was handled as a procedural effect in Houdini. The clouds were created in Houdini as well, adding another dimension to the whole sequence.

On board Aether, the crew has an interactive solar system chart, invented entirely by One of Us. The team started building it after the live action shoot of the scenes, allowing the performances of the actors and the script plot points to drive all of the design work for the sequence. “We incorporated all of the on-set interactive light in the design of the graphics so it felt coherent with what had been shot. The actors had rough on-set lighting trails to work to, but no direction or intervention from us,” Oliver said.

“The abstract starscape helps add dimensionality to the shots and fill the space the characters occupied, though it's not scientifically accurate with respect to our solar system. The production had a stand-in for the trails on set for actors' eyelines, which we replaced with digital versions, and as the planets were purely diagrammatical, they are mainly lit from within. We also darkened the original plates to create the feeling of being in space.

“The trick with this sequence was finding a nice balance between all the different components, making sure the audience wasn't distracted by anything ancillary. A lot of on-set lighting and rigging was removed, using a combination of CG and paint. Its elements had to be seen from multiple sides and angles, with the people within it and outside of it, with lots of interactive light.” www.weacceptyou.com

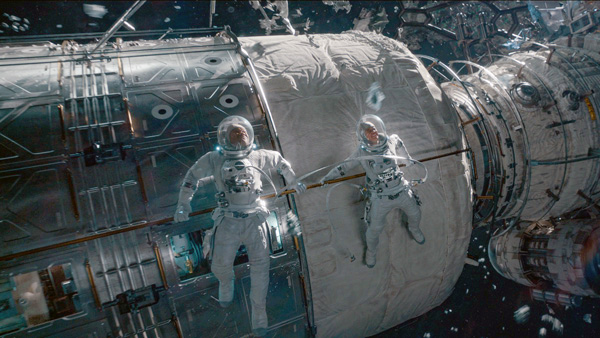

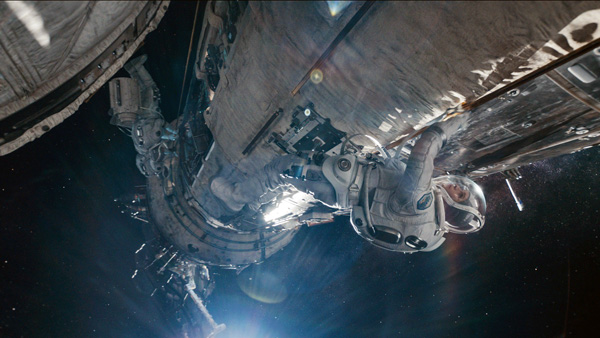

Space Walk

Framestore assembled a team experienced in science fiction to join production VFX Supervisor Matt Kasmir – VFX Supervisor Chris Lawrence from ‘Gravity’ and ‘The Martian’, Animation Supervisor Max Solomon from ‘Gravity’, VFX Supervisor Shawn Hillier from Star Wars: Episodes 2 & 3 and Graham Page from ‘Interstellar’. From studios in London and Montreal, they delivered nearly 500 shots. The team supported the story through visual effects that complimented the cinematography by DOP Martin Ruhe, creating CG facial replacements, building the Aether spaceship and interior, and the foreboding environment of ‘Sick Earth’, left behind after a global catastrophe.

To emulate zero-G and help to make shots of Aether’s crew, floating in space, feel more authentic, digital face replacements were required for the wide, full CG shots in the ‘Space Walk’ sequence. High resolution Anyma scans were combined with proprietary shaders to create convincing high-res digital faces, which were then keyframe animated. The Anyma capture for the performance gave them an animated mesh of each actor that could be used to drive animation, despite the need for detailed clean-up work, especially around the eyes and the mouth, to make it usable.

Chris Lawrence said, “We used ClearAngle's Dorothy and Eugene systems to obtain super high resolution scans of the cast. Dorothy was used early on for FACs poses and Eugene was used later to capture them in their full makeup and costume. We had a tracking and animation rig for the eyes, but the rest of the face was driven directly by the Anyma data. This was a philosophical decision we took early on because we wanted to be limited to the captured performances.”

From Shapes to Faces

Anyma generates very high-resolution data. It starts with scans of extreme facial positions to measure describe and understand the face, using these as scan shapes to automatically build a digital puppet. During the building process, a suitable generic bone structure of the skull, jaw and eyes is used as a set of constraints.

Taking an anatomical approach, Anyma considers bone data, skin data and the tissue between skin and bone, and goes from there by separating motion through space, from deformation. It divides the face into many small deformation regions and then learns how to use the input shapes to deform each area. To produce a coherent result, it also learns the relationship between each area and the underlying bone structure.

By combining area deformation with the bone-to-skin relationships, the user creates a realistic face and also gains an understanding of what the face is capable of. The system estimates a digital face shape, generates an image, and applies optical flow to optimise the differences between this image and the actor’s face until it reaches convergence. The result is an accurate mesh of hi-res geometry, a frame-by-frame reproduction of the performance. But it applies the mesh to a face objectively, without interpretation, and is not connected to the rig of the model built from the scan data, for animators. It only understands where each point goes over time.

“We treated Anyma as a faithful recording in 3D of the actors' complete performances,” said Chris. “Traditional motion capture just wouldn't have given us the fidelity, and the high resolution scans alone wouldn't have given us the performances. The only purpose of the eye rig was to allow us to correct eyelines and make sure that any imperfections in the capture data didn't leave us ‘stranded in the uncanny valley’. In practice, though, it took some extremely subtle work by the animation team, as the head, body and eye performances all needed to work in concert with each other and the rest of the facial recording.”

The head motion and eyelines were adjusted to work with specific actions and the position of the camera. In some shots the work was quite nuanced, enhancing eye darts and blinks while in others they made broader changes to head angles and eyelines. Nevertheless considerable sensitivity had to be used because even very small adjustments could quickly make shots feel broken.

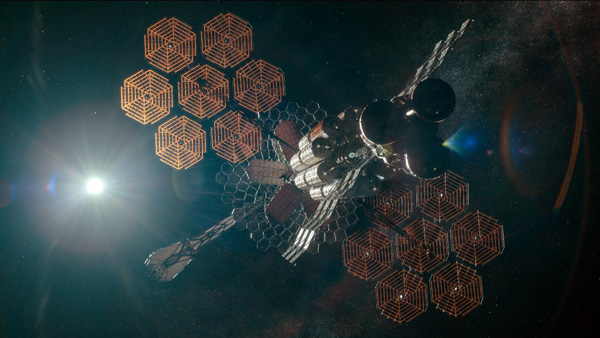

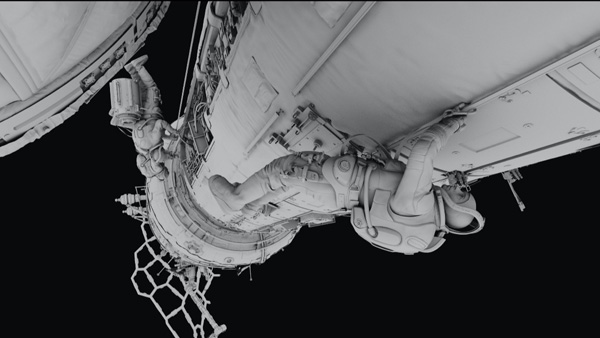

Aether

The Aether spaceship, housing the crew returning from their reconnaissance to Jupiter, is strangely beautiful and was designed by the Production Designer Jim Bissell who worked with Framestore’s Art Director Jonathan Opgenhaffen. “The ship’s components had to work practically – its beauty stems from its functionality,” said Jonathan.

Drawing from the studio’s archive of spaceship parts, Aether emphasises the futuristic feeling of the film while using recognisable engineering from today to stay grounded. Using parts of the ISS, for example, with existing NASA developments and 3D printing systems, the team then focussed on the details and texture of the ship to make it realistic.

Jim Bissell’s buzz word was topological optimisation. He wanted to create a plausible near-future ship. The central spine of the spacecraft was designed as a re-use of existing satellite design – the ISS truss work features, for example. Chris said, “The idea was that humanity was at a desperate stage and were willing to re-use tech where they could. The habitation quarters were made to be more like a 'tent', because this would be lighter and cheaper to make. The concept was that these new pieces would have over time benefited from algorithmic design that generates optimised structures that could be 3D printed in space.

“Jonathan worked with Jim and another art director called Stevo Bedford to realise the design. He imbued it with an incredible amount of detail that helped it come to life and gave it a tangible, realistic feeling – even though it was only ever fully realised as CG.”

The fact that Aether has to be partly destroyed and dismantled affected their decisions about the level-of-detail and the materials they used, but the destruction was a two way process. Chris remarked, “Destroying things is always fun! Obviously cloth was going to behave interestingly, and it's nice to see the layered materials and panels with different properties all smashing into each other. Those looks were all considered during material selection because, to a certain extent, the material properties dictated the look and feel of the destruction.”

Sick Earth

The Framestore team created ominous but subtle imagery to convey the idea that something has caused the global catastrophe behind the film’s story. Sick Earth is a huge character and is purposefully left ambiguous so that the viewer asks questions without necessarily receiving answers. Layers of clouds, some curling towards the sky resembling fingers reaching out to space, are the main cue for the look. This isn’t meant to be a natural phenomenon, so a degree of speed is visible from space. They experimented with FX passes in compositing to create additional movement.

The shoot of Augustine on earth took place in Iceland, with 110 kph winds and freezing temperatures, although the actual amount of snow posed some problems. Unfortunately, when the crew travelled over to shoot the plates, much of the snow had melted and needed to be replaced in the images. They had worked on snowy landscapes not long before for the first season of ‘His Dark Materials’, but now had the opportunity to push their snow shaders further to hold up in the many close-up shots of the snow moving across the surface of the ground, with the light scattered through it.

Monitoring the Monitors

Inside Augustine’s observatory, pre-production supervisor Kaya Jabar, working at that time at The Third Floor London, led a virtual camera shoot of the set, before designing a virtual LED shoot plan for the screens. Working with Chris, Kaya’s team created a suite of tools using Unreal Engine to tie together a virtual camera and an LED screen simulator that was accurate to the exact panels used on the day.

“Kaya worked with us very early on to visualise the LED setup,” Chris said. “I wanted to be confident that the screens would be big enough to cover the window gaps and far away enough to not suffer from any moire or other effects. She wrote a simulator that used real numbers acquired on a camera test to demonstrate when the LED screen would have visible moire or pixelation. She used the set plans and proved that the final design was going to work out. In hindsight it worked so well that we all wished we'd used it even more.”

Kaya said, “I do believe that we were among the first people to plan it that way. I just applied the logic that if we can virtually plan a shoot and show what will replace a green screen, then we can do the same with LED screens.” www.framestore.com