Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Melbourne turned Lewis Carroll’s book 'Alice in Wonderland' into an experiential exhibition titled 'Wonderland' that ran from April to October 2018. Instead of curating a passive museum-style display, the museum's directors and technicians wanted to take visitors on an interactive journey through Alice’s adventures. The resulting experience was designed and built with the help of a diverse group of artists and studios who specialise in installation, multi-media display, visual effects and animation.

For ACMI, the project was partly historical and research-based. The curators at the Centre wanted to show that as people lived through cultural, technological and social changes occurring since 'Alice in Wonderland' was published, they have continued to return to Lewis Carroll's book as a source of joy, wonder and inspiration for their own works of art. The exhibition illustrates ACMI’s continuing fascination with new visual techniques and the role of the moving image to make the impossible seem possible.

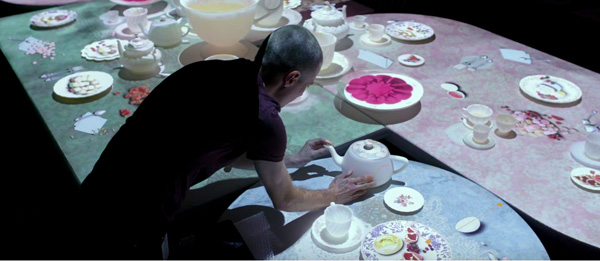

One of the most distinctive sections of the exhibition occupied a single room made into a complex, animated projection mapping project. Titled 'Mad Hatter's Tea Party', it contained a table surrounded by chairs and laid with everything needed for a traditional tea party – plates, cups, saucers, platters – all 3D-printed in pure white.

Time for Tea

As the visitors, who become 'guests' at the Tea Party, take their seats at the table, the fun begins. The walls come alive with landscapes, shifting from photoreal to surreal to fantastical. Plates are filled with spinning cakes, patterns, a shimmering jelly, video clips and other 3D and 2D treats, while an ant trail runs over the table top and the table cloth slips away.

This content was a multi-channel CGI video, projected and synchronised throughout the entire room. Content that was projected onto the walls was carefully synchronised with the content that was precisely projection-mapped onto the table, the place-settings and dishes. Combined with an audio track , the experience was highly immersive as each visitor watched and felt the environment change from a complete white room into something quite different as the four-minute video progressed.

Grumpy Sailor, a creative agency with studios in Sydney and Melbourne, was responsible for designing, animating and delivering the content. Their team created the projection-mapped CG animations and collaborated with various other artists who designed and built the table, brought the content into the digital projection software that would accurately display the video, and engineered the physical projection set-up at the museum using Panasonic projectors.

Blank Canvas

Katrina Sedgwick, CEO and Director of ACMI, described the Centre's vision for the Tea Party. “We wanted to bring to life the way that CGI is built layer upon layer, and decided the best way to do this would be to create a blank canvas of a ‘Mad Hatter’s Tea Party’ and projection map an entire room – slowly building up images to create a unique experience,” she said.

As the project got underway at Grumpy Sailor, their managing director Claire Evans developed a director's treatment, revealing the potential to tell their story as an interactive museum experience. She and the team discovered that building a 3D projection mapping installation on such a detailed scale that viewers could gather around - to look at from any angle – was going to involve some unexpected challenges. More often, projections are placed in front of the audience and viewed from one vantage point.

Grumpy Sailor's Creative Director James Boyce and producer Kate Bennett, who spoke to Digital Media World about the facility's work on the Tea Party, said, “We devoted three teams to the project – a story team developing the inspiration and purpose, a 2D and 3D design team creating visual material, and a technical team working on the physical installation. As problems were discovered and solved, the teams worked together through cycles of prototyping, testing and adjustments. This workflow meant they could keep making decisions up until the last minute.”

Layering Up

Grumpy Sailor worked with 3D artist Gerad Gray, initially with storyboards and animatics, to plan the project, design the interior and then finally build it at ACMI. Also working with the exhibition designer Anna Tregloan, Gerad modelled the objects that the imagery would be projected onto and had them 3D printed. Because these objects became the projection surfaces, testing the printing material was important as well to understand how it reflected, absorbed and refracted the projected light.

“Once Gerad had locked off the virtual assets in 3D in Maya, the objects were 3D printed, and the ACMI design team assembled all of the objects and fixed them in position on the table,” said James. “The 3D model was handed to a designer who applied patterns and textures to the virtual objects in After Effects, and an animator who created the motion graphics and camera moves. Meanwhile, a 3D artist worked on further 3D elements and animations, such as a table cloth that moves over the table, that would become part of the projected experience.

“All of these artists' 2D and 3D renders were then pulled into After Effects layers for compositing into exhibition files ready for projection. In the end, the artists produced about 120 layers of unique content. Keeping so many separate layers gave them a great deal of control over the final video files that each projector delivered into the environment, especially since each layer did not necessarily cover the entire scene – some of them needed to fit together, like a collection of precisely aligned garbage mattes, addressing parts of the scene.”

Installation

Grumpy Sailor's artists worked back and forth with designers at Light Engine, a company that handles projection mapping design and production for events, for exhibition spaces, to run the animations and layers in the projection software. To make sure the physical space and digital renderings were aligned, the artists projected a grid over the surface of the table and referred to a top down view showing what the projectors were seeing, which helped them understand the limits for the table animations and establish exactly where the objects sat, both 2-dimensionally and in 3D space.

On site at the ACMI, a lot of tweaking and adjustment had to be done. Pandora's Box, a layer-based real-time rendering system that supports live compositing in 3D space, was used for this final work. Able to accommodate projection onto irregular shapes, it allowed the team to adjust the position, rotation and scale of the projections, on the fly. It has integrated keystoning to compensate for the angled projections from the projectors overhead, and soft-edge blending to help combine the imagery from the multiple projectors.

ACMI's exhibition technicians sourced the projectors for the imagery from Panasonic. Although the projectors could not be customised specifically for the installation, ACMI did find models specialised for installations that suited their purposes – they could be mounted at positions and angles that allowed visitors to view the projections from any point around the table.

Switched On

Early in the development stage, ACMI supplied Grumpy Sailor's concepts to Panasonic's engineering team, who proposed a set-up based on their projectors. This configuration was then fed into the on-going design process, and from that point, laser light systems became a core part of Grumpy Sailor's image blending techniques. Panasonic's ultra short throw lenses made the whole system more flexible and gave them the ability to use wall projections to create and control scale in the room, for example.

For ACMI, a significant feature of this exhibition was the use of filmmaking equipment such as screens and projectors in unconventional contexts.

Therefore, being able to hang the Panasonic projectors, which need very little maintenance, as required in overhead rigs was another advantage. Aaron Marshall and Paul Rodger from Light Engine worked on the projectors for the project with Grumpy Sailor. Paul said, “The projectors were all mounted in a ceiling rig using custom-made ceiling brackets for the table projectors to allow them to shoot straight down.

“We also encountered challenges with available space inside the room, which we solved by choosing specific snorkel- type lenses for the wall projectors. These lenses allow us to mount the projectors very close to the screen surface giving us more flexibility. The projectors are actually facing 180° away from the screen surface while the lenses bent the light output directly back onto the walls. The two models we used were from Panasonic's Installation range - the PT-RZ660 for the walls and the PT-RZ575 for the table - chosen due to the availability of interchangeable lenses and also their brightness factors. grumpysailor.com