VFX Supervisor Dan Bethell talks about DNEG’s Mad Max journey with director George Miller, building vast, complex environments, crowds and vehicles with lives of their own.

DNEG was the main VFX partner on George Miller’s Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, delivering almost 900 shots across 27 sequences. Their work visualised George’s imagination and the richness of the Mad Max world for the audience. The DNEG team gave the production access to the speed, creativity and flexibility of 3D visual effects to make this story feel not only real to the viewer but also intensely dramatic and distinctive.

The starting point of their work was 16 environments – including Gas Town, Citadel, Bullet Farm and the Wasteland desert landscapes. They also created over 100 character assets including crowds and digital doubles with over 50 vehicles – major players in all of the Mad Max stories – including the hero assets War Rig, Dementus' Monster Truck and the Octoboss Glider.

Digital Media World had the chance to talk to DNEG’s VFX Supervisor Dan Bethell. “This was the inaugural project for our DNEG Sydney studio,” he said. “It’s been a wild ride. We set up the physical studio and built up our team at the same time as taking on this major journey with George Miller.

“We came on board in October 2022, just after the shoot wrapped in September and post got underway, and delivered in May 2024. It was a full 18-month project, involving our artists with lots of detail and looks to work out and worlds to build. Over the course of post, DNEG’s local team involved about 150 artists, production and support staff, just in Sydney. Globally, the project tapped into over 1,000 DNEG employees.”

Mad Max Lore

The Art Department had abundant material to share. Mad Max lore is endless, with generous amounts of background information that may never even reach the screen, but is there for the contributing artists, adding richness to what the team creates. “It’s incredible to discover the Mad Max: Fury Road storyboards of Mark Sexton, the comic books, looks from the original movie, vehicle designs from Production Designer Colin Gibson and the Art Dept. Everything is heavy with detail.”

Dan was not a newcomer to the world of Mad Max. He and Furiosa’s Production VFX Supervisor Andrew Jackson had worked together in Namibia on Fury Road some ten years earlier, which meant that Dan had all of that experience and material to refer to and expand on, as well as the new reference for Furiosa.

For example, the Citadel was also in Fury Road, but this time the artists would have a chance to realise new parts of it, seen in an earlier time. They expanded on everything from ideas to landscapes, not only the new Furiosa material but also Fury Road’s as yet unused backstories and lore, ranging from photography, plans, schematics and designs to character references and costumes. They spent hours digging through these references to find just the right character, leading to just the right backstory. Dan commented, “Everything in George’s world has provenance and purpose.”

Physical First

Nearly all of Production Designer Colin Gibson’s designs – mainly the vehicles and some set pieces – were physically built by the time Dan’s team started work. They accessed Colin’s build plans and lidar scans of the practical assets themselves. Many others had been fully designed, fleshed out and were ready for digital creation.

All of this material became their foundation and working palette for the project, and consequently, even those assets that they needed to build themselves from scratch in CG were inspired by Colin’s work. It called for a new way of thinking. Dan said, “The mindset of the Wasteland is that everything is salvaged, re-used and re-purposed. So we embraced that same philosophy for anything we built digitally, especially the vehicles.”

Landscapes with Character

Handling 16 environments within the time frame of a single movie required an organised approach, orchestrated for efficiency. While similarities existed between some of them – notably the expanse of the desert landscape – it was important to George to approach their looks as a constantly evolving palette for the audience as they travel through this story.

“Each one of those landscapes needs to have a distinct, memorable character,” said Dan. “So we divided and conquered. Each environment had its own creative reference and its own brief. Some, like Gas Town and Bullet Farm, had to be bigger and more complex, and became worlds where entire scenes take place. Others were more transient, like the crevasse where Dementus and his Horde hold a trial to select new gang members – a unique environment that needed a specific design.”

For scenes in exterior environments that used natural light and encompassed lots of camera movement, green screen was never going to work, and that meant extensive rotoscoping for the team to separate the characters from the backgrounds. “George and the cinematographer Simon Duggan like long, sweeping camera moves and choreography for which green screens are too limiting. Furthermore, the shoot locations often had too much vegetation or industrial objects encroaching into the frame. Some of the studio shots did employ green screen, but for most environments we just had to manage a lot of roto,” Dan said.

References from the Real World

Reconciling George’s vision and the scale and grandeur of that world, with a grounded, authentic reality – that defined their challenge. “Andrew Jackson told us that capturing the right look and feel meant first finding references in the real world for everything we build. For Gas Town, we visited a resin refinery just south of Sydney at Port Botany. We took lidars and photography, and captured interesting aspects of that place and its design. Then we used our captures to break down that place into a kind of Lego kit of pipes, valves, brackets and tanks, and used the kit to build up Gas Town into the monstrous industrial location that we see in the movie.”

As they tweaked the environment from shot to shot, they dipped into that collection to kitbash the Gas Town structures in a granular way. On that occasion, the set had simply been an open, concrete venue in western Sydney, dressed with some practical tanks and paraphernalia positioned in the immediate foreground for the cast to interact with, bang on. Anything beyond that would need to be replaced with CG elements.

On the approach to Gas Town, the gate structure itself was a practical build, while everything beyond it and to the sides was part of an extension. The team always tried to include practical elements in-camera, however small. It’s good for the cast as well as the artists, and enhances believability.

Open Cut Mines

On the other hand, the Bullet Farm was about portraying large open cut mines, which are typical of western New South Wales where Furiosa was shot. The idea of those thousands of people at the Farm digging resources out of the ground was clearly a theme of the story. A small industrial complex featuring a smelting chimney stood at the centre. Otherwise, it was just rock, and worked rock, with all the associated contrasting textures and natural materials that are found in mines.

Dan said, “Our challenge for this environment was creating something believable that fit the huge scale of this world, and was able to accommodate the big scene that unfolds there. It starts with an ambush and works its way down into the Bullet Farm, following Praetorian Jack as he drives the War Rig, ramming through the great chimney structure Dementus stands on top of, causing the cascading domino effect and ending in the central collapse.

Cameras on the Move

"The end of the scene sees the War Rig falling down into one of the pits, before Furiosa rescues Jack and they ride away. “Making sure we had an environment that would tie all those pieces together and form a foundation for the story – making all that would run smoothly was both a creative challenge plus a huge logistical puzzle to allow George’s cameras freedom of movement for the action.

“It should feel effortless for the audience, who takes over the camera’s eye. That was a challenge we faced throughout the film. The stowaway sequence, for instance, is another example. This time it’s a big chase sequence, 15 minutes long with 240 shots. Effectively, it unfolds on a big open plain but, in fact, the infamous War Rig becomes the environment. We go under it, onto its 5th wheel, on top of it, then up in the sky above it. George turns the whole vehicle into the stage for this sequence."

Wastelands

The vast Wastelands and deserts in Furiosa leaned heavily on looks from the Namibian deserts where Fury Road was shot. “Also working with Andrew on that production, I was more involved with the shoot. Andrew had shot tens of thousands of images from the sets in Africa of real environments and deserts from salt flats to dunes to gritty earth. We could use those images to transform the shots recorded for Furiosa in NSW with the right kinds of sand and scree.”

New, specialised techniques were used on this film, such as machine learning at Rising Sun Pictures to blend characteristics of the face of the very young Furiosa with those of the older actress (Anya Taylor-Joy), especially in the shape and performance of the eyes – where the audience would be looking most. Pre-vis and post-vis were also a key part of George’s process as he worked through shots in pre-production, from long before the shoot and through production and post, working with a dedicated team at Kennedy Miller Mitchell production company in Sydney.

Logistical and Creative Effort

“However, for DNEG’s 880 or so shots, there was no single or straightforward solution,” Dan said. “It was a matter of combining focussed work and almost every tool we had knowledge of – Furiosa was a logistical and creative effort that exercised every part of our collective experience. The artists needed both creativity and flexibility. For instance, the hard surface modellers had to push their skills across dozens of different vehicles and 16 environments while managing greater scale and complexity than had been required on any single show before.

“For me, probably the best part of it was the collaboration we achieved. George has great vision but the execution was open to interpretation. The production needed a team to sort through the timing, composition, looks, colour and other aspects in a precise way – and that became the focus of our work.”

Skies, and the lighting associated with them, became important, and not only because of the intense, distinctive light of western NSW. George tended to shoot long scenes over multiple days, during which the skies and lighting would change. But the sequences still needed to feel consistent and tied to the same places, and avoid confusing the audience during fast action to support quick cuts in the edit.

“Often, the skies also loomed very large in the frame over the flat landscapes. Therefore, as well as consistent, they needed to be rich and detailed and serve as a feature of the story. We replaced many skies to produce a continuous aesthetic experience between the environments, skies and characters from the beginning to the end of sequences,” said Dan.

Pedal to the Metal

The onscreen visualisations of almost everything took on character-like qualities, and this was especially true when it came to building the vehicles, always among the most exciting, anticipated aspects of a Mad Max movie. Furiosa doesn’t disappoint. Here, the hard surface work became a modeller’s dream job. As mentioned, most of Colin Gibson’s Mad Max vehicles were built practically before the VFX teams joined post production. DNEG was responsible for replicating a number of these as full digital re-builds.

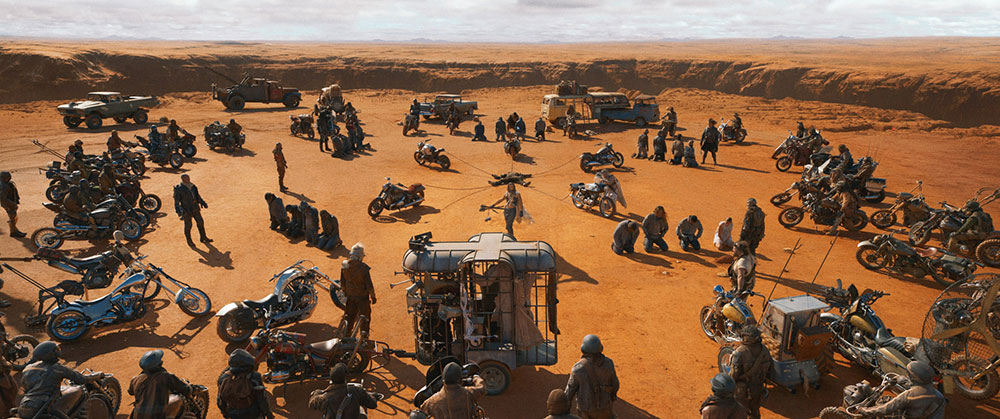

Unlike Fury Road, motorbikes are important vehicles in Dementus’ world. He drives a 3-bike chariot himself, and is followed around by a 2,000-strong digital Horde riding a fleet of bikes, all brought to life from scrap parts and pieces. Dan said, “What’s especially interesting about those motorbikes and riders is the use of motion capture animation. Andrew Jackson oversaw a capture session where he recorded the motion of the performers, as well as the bikes they were riding. We found that by capturing a biker’s distinctive transference of weight, shifting centre of gravity and bike-to-rider interactions, we could add that motion to our 3D elements, making them more compelling to watch.

Monster Truck and War Rig

“The huge 6-wheel Monster Truck that Dementus rides to chase down Furiosa and Jack after the ambush, and the War Rig were built and driven on set. We re-created them in CG in order to gain enough control over them in the creative, fast action, even dangerous shots and sequences. The replicas had to be precise enough, down to the last nut, bolt and seam, to support invisible digital takeovers, as the shots repeatedly swapped between the live action and digital assets.

“The War Rig, essentially a petrol tanker, serves as a travelling shrine to Immortan Joe and his opulence in this film. Looking shinier and newer, of course, than in Fury Road, its embossed designs down the side of the tank tells his story. It was quite beautiful in real life. Given its size and reflectivity, we relied on the replica for cleanup and reflection enhancements.

“We would simulate travelling effects like spinning wheels, and add flying dust. Using them meant the production could remove a section of the cab to position the camera up close to the actors, for instance, and then we could add that section back again digitally in post.”

The replicas became very useful tools when staging action shots. The team could accommodate stunts by removing safety mats or adjusting parts of the body in post when stunt actors needed to fall on it. They could replace just the cab or just the tanker, or set the bommy knocker spinning, leaving the rest of the asset in place in the shot. “The replicas made designing the action shots much more convenient for George – again, we were balancing the logistical with the creative. He could do whatever he wanted with the vehicles, without compromising the shot,” said Dan.

"In the spirit of the Wasteland, adding more vehicles to the fleet involved re-using parts of the existing ones. The kit-bashing aspect of building out the fleet was quite fun. The wheels would be borrowed from one of the existing vehicles, the axle would come from another, and the chassis pulled from another. Tyres, windscreens, engine blocks could all turn up in another vehicle, elsewhere."

Getting Airborne

The Octoboss Glider was one vehicle that never existed practically. The motorbike – a Harley Davidson – that it was based on was ridden on set and captured in shots, but all rigging and the kite structure was fully digital. Trying to find reference and inspiration for such a massive parachute, able to support the weight of this heavy bike while keeping the nuances and subtlety of real chute material, was interesting.

Dan said, “It was largely a matter of researching kites. As the Bondi Beach Kite Festival was happening at the same time that Andrew was collecting reference to send us, he had gone along to shoot some massive kites there with long tentacles trailing down. These made the perfect reference for the Octoboss.

“Earlier on, Colin had thought about making the whole bike fly, but eventually George convinced him that the bike belonged on the ground, while the CG team could let the huge kite asset do the flying.”

Gathering Crowds

DNEG created digital doubles that were used in several ways, although they were not intended to ever be noticed. One way was to replace stunt actors, War Boys and, in fact, most members of the cast. Using the digi-doubles for digital takeovers allowed them to carry on through those impossibly dangerous performances Mad Max is known for as they jumped and fell off vehicles and interacted with the huge set pieces.

DNEG also needed to create large crowds in many sequences – Dementus’ Horde, the Gas Towners, Bullet Farmers, as well as the Wretched and Dispossessed in the base of the Citadel. “Just about every large-scale shot with large numbers of people needed some kind of crowd enhancement,” Dan remarked. “We aimed to localise our techniques to support the camera work and set builds, starting with the extras present in the shots.

“In the same spirit as the green screen challenge, due to the production’s dynamic camera moves and the scale of the scenes, traditional 2D replication wouldn’t be enough. You would quickly notice repeating patterns in the crowd and need variations. More important, though, was the fact that the crowd had to walk over and into terrains that don’t exist in the real world. For instance, the majority of the Citadel is digital, including the causeways.

Single Approach

“So it became simpler to focus our effects on a digital crowd with digital FX, giving us a single approach for the whole of the environment. It made us more flexible while tying everything together, and gave us a chance for some creativity. For instance, when building up crowds we could add our own freakish looks to crowd characters to show the effects of their hard, post-apocalyptic lives.”

Capturing cyberscans of stunt and other actors made it possible to generate full 3D characters who could do almost anything safely – from principle characters down to non-descript background figures in a range of costumes, all animated with either keyframing or motion capture.”

Thinking about this monumental project he has achieved with the team at DNEG, Dan reflected on what working with George Miller had been like. “Completing a project with George always feels like a journey,” he said. “He’s an entirely story-driven director who keeps his stylistic choices grounded firmly in reality. All visual effects the team creates feed into the bigger picture, and ultimately help to define the story the production is telling.” www.dneg.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor

Images: © 2024 Warner Bros. Pictures. All rights reserved.