DNEG’s Aleks Pejic talks about the team’s creature FX and animation work on Godzilla, Kong and a new monster, the Charybdis, for ‘Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire’.

DNEG delivered over 310 VFX shots for the latest Monsterverse film, ‘Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire’. The team worked on 20 sequences, building environments like the Pacific island base, the Iwi Realm and the crystal pyramid as well as the Veil vortex FX sequences. But above all, DNEG’s artists had a chance to work on the monsters themselves – King Kong, Godzilla and a new creature, the Charybdis.

DNEG had three VFX supervisors assigned to the project – Paul Franklin, Aleks Pejic and Lee Sullivan, with Etienne Daigle working on set for DNEG. Digital Media World talked to Aleks about working with these huge creatures who loom large in the minds of people who love monsters, as well as on screen.

Coming into the existing Kaiju Kong / Godzilla (Monsterverse) franchise of films and TV series meant DNEG was handed the models for the two principle monsters, and then needed to work out how to align them with their render and animation pipelines, fur and shading tools and adjust their calculations to be able to control the final look and motion. Achieving a perfect match with the creatures’ established look in the other films was essential, as well as preparing them for the all-important fight sequences including the impressive battle between the Charybdis and Godzilla in Rome that opens the film.

Monsters Inside Out

Motion forms a key part of each creature’s recognised look, so when tackling the animation, it was worthwhile getting to know Kong, Godzilla and the Charybdis through the way they moved. The filmmakers themselves know their creatures inside out, and recognised what they would or would not do. Aleks said, “Our animation supervisor Spencer Cook had taken this same role for the earlier film Godzilla: King of the Monsters. His familiarity with the physics that made the characters distinctive was a great help, but it was still never easy. We were inhabiting a new environment and situations where we couldn’t just switch on the Godzilla run cycle, for instance, and expect it to work.

“Each scene required ensuring the audience can feel the weight of the monsters, and read the personality constraints on their moves. The director might say ‘That’s not a chimp – that’s Kong’ or single out a certain move and comment, ‘Kong would never do that’. Because these creatures are singular and occupy their own world, all animation was keyframed for all sequences.

“The animation rigs were complex, but not unexpectedly so. You have to appreciate that the creatures are huge. You can scale up a rig just so far, maybe 20 to 30%, but after a point you are faced with a need for more complexity. Here, we were dealing with creatures 100 to 300 times larger than any existing animal.”

A critical part of the motion aspect of the monsters were the muscle simulations and skin deformations, which are all driven by the motion. Getting these looks right meant talking over the production’s artistic expectations with VFX Supervisor Alessandro Ongaro and Adam Wingard, the director. For instance, certain traits like flesh jiggle would be subjective, so they would ask – what looks right to YOU in a creature of this size? These are ‘super’ animals, heroic in their way. They have to be believable, consistent and fantastic – all at the same time.

Ziva – Simulations, Deformations and Emotions

DNEG had been working for some time with the developers from Ziva Dynamics and finally acquired their software in April 2024. Starting with a creature’s bone, muscle, fat and skin geometry, Ziva is used to simulate soft-tissue materials and apply real-world physical properties to simulations. With Ziva’s materials feature, artists specify attributes such as flexibility, volume conservation and density, and then connect their simulations so that they react and collide with each other as they would in real life. Forces can also be defined for deformable elements like muscles. It saves time by reducing the need for sculpting or correcting shots, relying instead on physics-based simulation.

For ‘Godzilla x Kong’, they mainly used Ziva in the traditional sense of driving simulations and deformations over the full body and face. Interestingly, at the time of making this movie, they were also working with the developers on new functionality – a machine learning tool for facial expression capture and animation.

While the monsters don’t speak, the story called for a certain amount of emoting and communication between them as they collude to take down the tyrant Skar King and his army. As a mammal, Kong can be expected to be able to show emotion. But Godzilla is a reptile, almost expressionless except for his eyes, which the team relied on for any emoting especially during the fights. Also, in one sequence we have Kong undergoing a tooth extraction that shows him suffering in extreme pain. The pacing of the sequence goes slowly, which made his expression important to keep the audience engaged.

Aleks said, “Ziva’s new machine learning facial procedure involves scanning an actor’s face and then carrying out a specific 22-minute session in a 4D capture set-up, where the actor performs particular lines that encompass the moves for all sounds. The captured motion is imported into Ziva, which uses it to train the rig built for your creature or character. The rig not only learns the constraints and limits for the character’s performances but also the in-betweens, improving on the traditional FACS system by producing more coherent, smooth transitions that appear natural and closer to a real performance.

“We worked with Ziva’s developers and a group of animators for about a year on this process. They needed feedback from experienced animators who have been using FACS for over 20 years and were finding it challenging to change over to a new tool.”

Managing Size and Scale

The size of the monsters made shot design both an interesting and challenging aspect of this movie. During production, the crew had made great efforts to frame the shots without a clear impression of exactly how the creature was meant to fit into the scene. “It was hard at both ends of the image-making process – for the crew and for us,” Aleks said. “Managing scale had to be addressed shot by shot. We had to adjust the framing – say, by about 10% - fairly often.

“Although having more flexibility would have been useful, there was no scope for really significant changes in the framing for these creatures. Any adjustments would have a major impact on how we handled the underlying FX – muscles, fur groom and so on, and re-framing always had to put story points first. The plates weren’t to drive the movie – they were a tool to storytelling, an ingredient contributing to the final mix.”

Lenses were important to the filmmakers for creating the look they wanted for their film, but added more complexity in post because they were as likely to distort an image as enhance it. Like any other element on screen, Kong’s look is in part defined by the lens. Its effect on his face, for instance, is critical to how the audience perceives him.

Scaling Interactions

Most discussions involved scale to some extent. Aleks said, “Interactions of all kinds – from destruction of the environment to splashing water – had to take the huge size of Kong or Godzilla into consideration. But meanwhile water is still water, with recognisable looks and behaviour. We also needed to be aware that Ziva is meant for realistic animals, not giants. We built all of the skin layers and muscle systems that Ziva needs to drive its simulations, and proceeded carefully.”

The fight in Rome at the start of the movie between the Charybdis and Godzilla – where much of DNEG’s work was focussed involving water, destruction and creature choreography – is an example of the complexity of building scenes that included the monsters. They broke down the action to define the animation, what was causing the animation and in turn, what it was causing to happen.

“We would send the fight animation to the water or destruction FX team, as usual, but we would then need to

ensure that those FX served the story, were visible in the midst of the fighting, that the faces were visible and readable, and so on,” said Aleks. “In the end, we may have had to go back and tweak the animation, causing a new wave of interactions.”

This fight was also the sequence DNEG worked on that relied most on previsualisation, partly because of the need for aerial photography. “We needed previs in order to communicate to the pilot and cameramen precisely what we wanted. We had to apply for aviation clearance and so on. But beyond that, so many sequences hinged on each other, and we couldn’t previs everything, due to time and budget. Even with previs you don’t know where the story will take you by the time you get to that scene. You may well need to change much of the original plan,” Aleks said.

The Charybdis

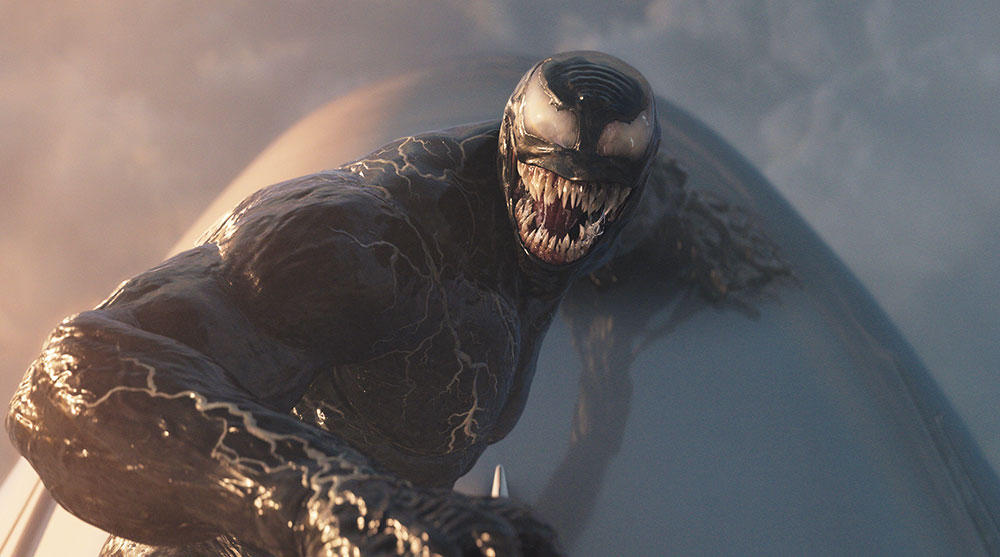

The Charybdis had been designed by the client in pre-production and DNEG had the job of building and animating the model – a creature with six legs and tentacles, covered in razor-sharp scales and looking very different to Godzilla. When these two monsters engage in a vicious fight that ends by defeating the Charybdis, the production especially wanted to highlight the contrast in looks.

“After the shoot, we realised that the expected colour palette used for the model was going to blend into the colours of the plate too much, making the whole creature difficult to read,” said Aleks. “Also, the director wanted a look that featured brighter colour with more pronounced textures. Before, the Charybdis had been too familiar and naturalistic. We made several versions before settling on the final one.

“The animation for our Charybdis was not so challenging – again the challenge came from managing its scale, and choreographing how the two huge, contrasting characters would meet and clash in the shots. Their textures were important but the scale made them a challenge to portray. Lighting textures had two possible goals. We could either match the plate – which was easier because because it gives you clear boundaries to work inside – or match the artwork we were working from.”

Lighting Textures

Many of the fight shots that were all-CG needed to follow the artwork. For example, Kong is covered in dark grey fur which they varied with light penetrating the fur groom. Godzilla is also grey, presenting enormous surfaces across the screen with not much to hold on to visually except displacements and texture details. They looked for ways to add interest and nuance to the surface with lighting and small amounts of colour.

At that point, the work became creative. “The Rome sequence was given a sepia look, which created variation when combined with the grey,” Aleks said. “The plates had been shot at different times of day to fit with air space restrictions above the city, leaving us the task of recreating a consistent lighting scenario that made the most of the sequence. The angle of the light largely determined the look of those shots, changing the sheen on Godzilla’s scales and emphasising different features of the monster.”

Aleks believes that to help build a story, shots must look good to the eye as well as possess continuity and deliver action. “This was our aim for Godzilla x Kong’, he said, “It has been a fun, satisfying movie to work on, and not only because working on monster heroes like Kong and Godzilla is something I have always wanted to do.” www.dneg.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor

Images: © 2024 Warner Bros. Ent. and Legendary. All Rights Reserved. GODZILLA TM & © Toho Co., Ltd.