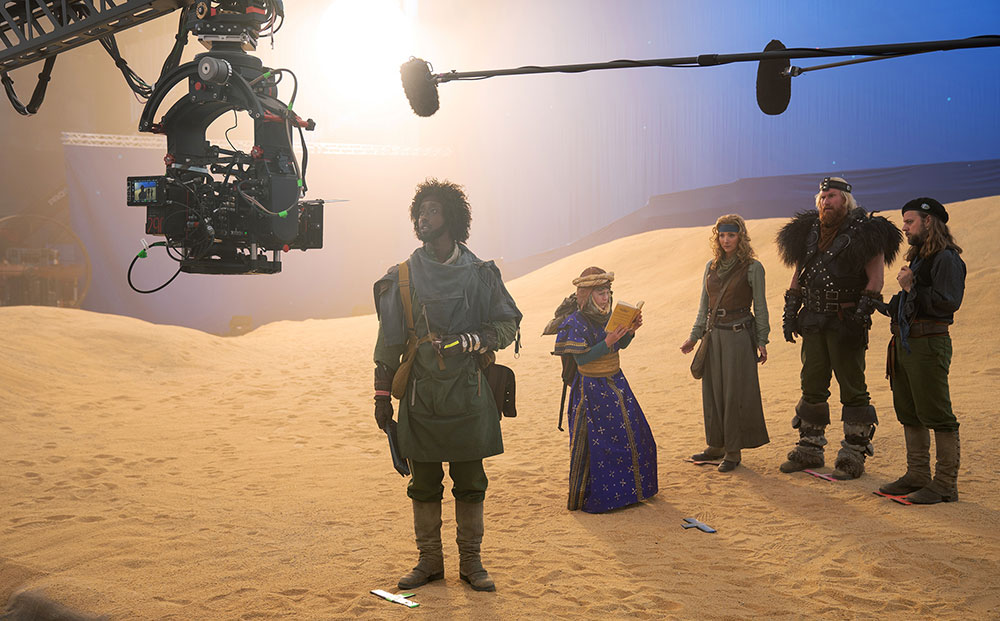

James Dinsdale, Virtual Production Supervisor at Dimension, talks about the virtual production system for TV series ‘Time Bandits’, immersing viewers in 15 authentic worlds across the show.

Director Taika Waititi’s vision for his 2024 adaptation of Terry Gilliam’s film Time Bandits as a series for Apple TV+ was ambitious. Keeping up with the story of a boy who loves history, and discovers a time-travelling portal in his bedroom, would need some 15 different environments, crossing not just continents but also historic eras.

It had to accommodate humour but still be serious enough to immerse its audience in a new, authentic world each time, and achieve all of those goals within a TV series time frame. It proved to be a good opportunity to take advantage of virtual production.

Here, James Dinsdale, Virtual Production Supervisor at Dimension Studio/DNEG 360, talks about his team’s work on the show’s fast-moving production. “Because the series spans multiple time periods and locations, from Viking-era settings to 1920s New York, the biggest practical challenge was the sheer number and diversity of environments, about 15 in total, that had to be created. Building physical sets for each one would have been impractical and costly, making virtual production the most practical choice to bring Time Bandits to life,” James said.

Flexibility Factor

Dimension’s Virtual Production Onset team was able to adapt quickly to the director's vision and the changing demands of the story. The flexibility factor, and their ability to create and rapidly change environments, became the biggest advantages they brought to the project. “We could even switch scenes around over a lunch break. That freedom wouldn’t have been available to us using traditional methods,” James said.

“One such instance involved reworking a scene in a Mayan village to take place in a new location in just 45 minutes. On another occasion, an environment depicting a Harlem nightclub rooftop in the 1920s was changed to a completely new environment – the docks of Brooklyn – within a two-week turnaround.”

The entire production, including setup and tear-down, took nine months, starting with the creative teams working during the first three months with the VFX Supervisor Tobias Wolters, the Production Designer and Art Directors to hone the digital environments and look. Following this, the team were involved in setting up the stage and workflow a month before shooting began. Then they stayed on a few weeks after wrap to pack down.

On the Sets

In purely practical terms, using Virtual Production (VP) also made the shoot more efficient, allowing faster decision-making and faster transitions between environments. The technical infrastructure reflected the production’s priorities – flexibility and speed of configuration as well as precision.

The virtual production stage was in a horseshoe-shape, 22 metres in diameter and 6 metres high, built of Roe BP2V2 panelling with a pixel pitch of 2.8mm. The crew were shooting on ARRI Alexa Mini LF cameras, meanwhile following the relative position of all elements of the stage throughout the shoot with Vicon’s tracking software Shōgun, which was able to track a large number of objects out to the edges of this very big volume and analyse fast movement.

“This gave us quite a flexible camera system in the volume and helped us keep up with fast scene changes, such as in the Mayan village scene where the lack of time meant adjustments had to be made on the fly,” said James. “We didn’t set up an LED ceiling, instead using traditional lighting fixtures above for a more filled-out spectrum of light coming from the sky in the environments.”

Previs, Content Creation and VFX

James’ Virtual Production team worked alongside the show’s visual effects team from the very beginning. “Dimension was heavily involved in content creation both for previsualisation and in-camera VFX, and we operated the volume on set,” he said. “We started by reviewing the references from Tobias – imagery he had shot around New Zealand, plus maquettes and miniatures – to help us get the content creation process underway.

“In the early stages, we constructed virtual environments that were used in pre-production for previs. These environments ranged from the ice age to Mayan villages to Stonehenge and gave the production a chance to explore those places, establish best camera shots per scene and so on.”

Meanwhile, artists were working on virtual environments in Unreal Engine, as well as bringing in scans of physical sets and objects and replicating them digitally. The collaboration involved the art department, production designers and even the lighting team.

Once shooting began, the ability to create and switch between the wide variety of environments quickly came into its own. For the car chase, for example, the sequence had to be rewritten just before shooting due to space constraints on set. James said, “To make it work, we used the background footage in a continuous loop to make the cars appear to be racing down a city block, overcoming the limitations of the real-world set and delivering on the director's vision. Later, this was actually written into the script as part of the story, adding a humorous scene where the actors could only turn one way.”

The ability to blend physical sets with virtual elements helped maintain consistency across different environments, which is why scanning the production’s physical builds was necessary, digitising them for further manipulation. “Further to that, it was critical for the team to align their work very precisely with the production designer's physical builds when they were digitally replicating the set pieces, making them consistent enough to work directly with the LED wall,” he said.

Confidence in a Virtual World

The car chase sequence, in particular, demanded that the team manage camera angles and positions very carefully to ensure the digital and physical elements worked together smoothly without glitches or overlaps. In fact, their ability to achieve precise alignment helped the director gain more confidence in the possibilities of VP and led to regular discussions about how to ensure they were matching his vision.

Throughout the shoot, Waititi’s involvement and trust in the VP process grew as he saw the flexibility and creative opportunities it brought to the shoot. He started coming up with his own, additional ideas and leaned more on the team’s capabilities to execute them quickly, further enhancing the Time Bandits story.

The virtual approach also helped the team to achieve interesting dynamic lighting adjustments for scenes like Stonehenge, where both the sunset and the stars needed to be exposed correctly at different moments in the story.

James said, “Virtual production did introduce a few new challenges as well, which included figuring out a way to shoot on around 40 different lenses. Ultimately, this meant recalibrating the system in order to switch from the anamorphic lenses used in the first two episodes, to spherical lenses for the rest of the series.”

Where in the World?

In thinking about when and where his team’s main challenges arose, James considered that the ice age village took special attention because the vast majority of the episode was filmed within the volume. “The sequence had been rewritten over the Christmas holidays, and because of that, many details in the digital scenes had to be edited just before shooting,” he said.

“Even so, many scenes across the show could be left pretty much as they were captured in-camera, requiring little post-production. For instance, in the ice age scene, only minor elements like breath condensation were added later, and in the driving scenes we needed to adjust the reflections.

“But above all else, the 1920s New York scene-change I mentioned earlier – switching the environment from a Harlem nightclub rooftop to the Brooklyn docks – was one of the most visually striking and creative achievements in this project, and it was created within only two weeks.

“The whole rooftop scene was very quickly redesigned into a riverside dock scene by a team of artists who reconfigured or upscaled existing elements from the rooftop and combined them with new custom-built river and dock elements.” dimensionstudio.co