One of the biggest monster movie splashes in cinemas this year was 'The Meg', a blend of sci-fi, adventure and action about the most massive shark that ever lived. You might argue that such a story could never happen but visually, this production had to engage the audience with photoreal, believable looks – plus epic thrills.

DNEG's Vancouver studio contributed 390 VFX shots to the production. Their VFX supervisor Raymond Chen and other members of the team talked to Digital Media World about the work involved, which included the ocean environment at various levels below the surface, deep sea creatures, underwater vehicles, and water effects ranging from surface effects to underwater light behaviour. Achieving the necessary looks didn't rely on a particular technique or set of tools, but on thorough research, experimentation and many iterations.

To the Rescue

From an underwater research facility called Mana One, three marine scientists in a submersible vehicle undertake a mission to explore an extremely deep section of the Mariana Trench concealed by a cloud of gas, forming a thermocline that effectively prevents creatures from passing into or out of this region. The mission goes well until a massive creature hits their submersible, causing it to lose contact with Mana One.

A rescue diver is hired to rescue the team, due to his earlier experience attempting to rescue a submarine from a giant, unidentified creature.

Back at Mana One, the crew discovers that the creature is a megalodon – an extinct species of mammoth shark - that has escaped from the trench through a hole in the thermocline that the submersible had created. A small group manages to track and poison the megalodon, but a second, much larger megalodon emerges and kills the research party.

This kind of science fiction adventure story naturally calls for a huge range of interesting visual effects. Filming took place at Hauraki Gulf near Auckland, New Zealand, both on the Gulf itself or in water tanks equipped with very large green screens. DNEG had not been involved at preproduction but travelled to the set during production, which was completed back in January 2017, to gather set reference from both the tanks and the location.

Constructing Mana One

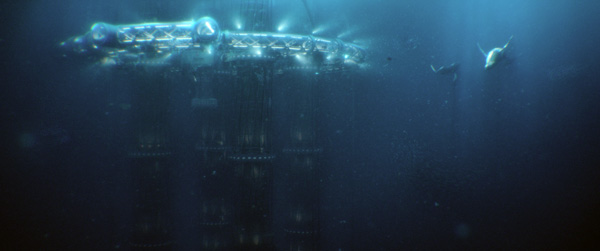

Raymond said, “We built the Mana One research facility exterior as a complete 3D asset, a large structure constructed on stilts out at sea, and rising to a height about 60m above the surface. The design followed models and schematics from the Art Department that were loosely based on a conventional oil rig. This asset was used for establishing shots showing the complex structure and shots of helicopters approaching.

“We built the complete lower level of the facility as well, an elaborate underwater observation centre, and although the upper and lower sections of Mana One never appeared together in any shot, they had to feel related and work together in terms of storytelling. The observation deck is designed as a steel and glass doughnut-shaped structure. A partial set had been built for it – except the set piece actually had no glass. Creating and compositing the curved glass walls into the plates was one of our team's responsibilities, based on a single sample section of the material, handed to us from production.”

Most of DNEG's shots, in fact, were in underwater sequences that revealed the environment and life under the sea at different depths. Although mainly a high action adventure, the director Jon Turteltaub and production VFX supervisor Adrian De Wet wanted to support the movie's science fiction elements by making both Mana One and the undersea world as realistic as possible.

Life in the Mariana Trench

Instead of building isolated views of the ocean floor per sequence, the team started with the geometry that had been set up for previs to build one, coherent submarine environment. Building the entire geography allowed them to accommodate the camera work, which could be plotted out in advance, without losing continuity.

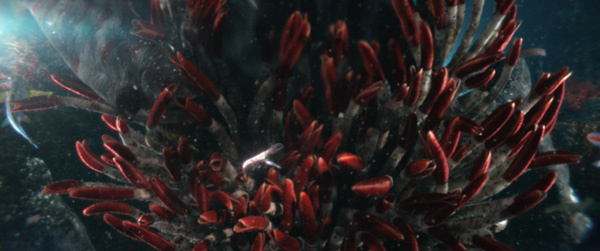

In the region of the Mariana Trench the marine scientists are researching, hydrothermal vents send plumes of superheated water into the cold, dark trench. Led by CFX lead Dameon O'Boyle with animation leads Ricardo Silva and Justin Henton, DNEG's artists received plenty of reference for the marine animal species and their looks, behaviour and physiology, and the behaviour and look of the light at these depths.

They also contributed to the concept art for the sea life, starting with real creatures as reference but tweaking the source material to make it look as if a separate branch of evolution has been developing over time in unexpected ways. They modelled and animated the movement around the hydrothermal vents, generating tube-worm colonies, coral clusters and numerous other creature populations.

Submarine Giants

Animation lead Ricardo Silva said, “For our creatures like the ghost sharks, cusk-eels, tubeworms, snailfish and so on, we looked at a lot of scientific videos. These creature are presented in the movie with more realism than the Megalodon, so looking at National Geographic Channel and documentary footage, which are easy to find, was the best way to achieve believable animation. For the Meg itself, our main character, we looked at great white sharks for the overall style of swimming and how they attack prey but also studied bigger creatures like the whale shark to get a better sense of weight and size that the character needed.

“Actually we always start with a realistic base and try to keep it was real as possible, but sometimes things need to be pushed beyond reality to make the scene memorable. Sometimes it is just a little thing like opening a jaw more than is possible in a real shark, other times it's something more noticeable like making the shark swim really fast to keep the action and pace of the scene exciting.”

One creature that they didn't find so much reference for was a giant squid that wraps its tentacles around the pod of one of the characters. From her point of view, the audience gets a close-up look at the underside of the tentacles and their suckers pressed against the glass. Two species of giant squid actually do exist, and DNEG's squid blends characteristics of both. The tentacles were especially tricky, but Adrian De Wet managed to find an unusual stock photo as reference, showing people pressing up against glass in a way that illustrates the effect of the compression and the way the flesh changes colour.

As Ricardo mentioned, DNEG produced shots featuring the giant shark itself, using the original asset built by Scanline. In particular, some of these shots show the shark outside the glass observation deck where it tries to take a bite out of the glass. DNEG needed to re-build the asset somewhat to work with their lighting system based on Clarisse interactive look development and lighting software.

Light Balance

The environments always needed to be effective for drama. Getting a consistent, realistic but interesting underwater look between the different environments that concern the story was essential. Down to about 100ft below the surface where the observation centre was, sunlight is still visible and made the task more straightforward.

But the deep sea, where the story's heaviest action takes place, was more challenging. “The deeper depths are where visibility degrades, surfaces are corroded and colours become leached,” said Raymond. “To support these looks, we added severe lens artefacting, distortion and colour aberration, and to differentiate the atmosphere, they created levels of murkiness and silt.

“It was important to use whatever lights were available in the underwater sequences effectively. The vehicles have lights of varying brightness that worked differently at different depths below the surface. First, we would figure out how the lights would look and behave in the real world, and adjust that look in a way that used the light to show off the environment according to the story.”

Water FX were always going to be part of this movie, not only down below the surface with the creatures and vehicles, but also effects on the water surface. For wide shots around Mana One, they took a 2D approach by shooting quantities of water surface and sky tiles around the Gulf. For closer shots, they needed to use more 3D water simulations, for example, for the water interactions when gliders launch from the Mana One. This way they could address specific wave heights around the built glider bay to add realism to the composited shots, using live action of the gliders after keying out the background from the dry green screen shots.

Getting Around

The characters get around underwater in several types of vehicle - one-man gliders, submersibles for a small group, and bigger submarines. The designs came from production and were either partially or fully built for the shoot. The gliders were fully built as practical props and shot on gimbals on an appropriately lit, dry green screen stage with the actors inside. DNEG's work then involved compositing the live action into their underwater environment.

The submarines, on the other hand, which could hold several people, were only partial builds. Because their design changed several times during production they ended up as almost entirely digital assets in the movie. The submersibles were more of a story point because the main scientists use one to travel down into the trench. Built for research, they have an unusual design with a spherical front section and arms extending outward. Only the hatch was built physically – the rest was created in CG.

“The challenge of getting the vehicles to move in the water as the director wanted was primarily about speed. Real world submersibles do not go very fast, but many shots required speed for story reasons. The difficulty was balancing faster velocity with preserving a realistic sense of weight and density of water,” said Raymond.

Ricardo also said, “For the animation of the vehicles, we always started with a general motion that is needed to tell the story. We make sure that it reads well and that the audience can understand what is happening. Once that is established, we worked to adjusted the physics to better should the weight and the properties of underwater motion. There is no particular tool for this, just many hours of work and iterations until it feels right.” www.dneg.com

Words: Adriene Hurst

Images: Courtesy of Warner Bros.