Netflix series ‘The Witcher’ about a monster slayer not only needed vicious, photoreal 3D monsters, it also needed precise choreography between them and their live-action hunter Geralt of Rivia and the practical and CG elements of each shot.

Cinesite London delivered over 250 shots that appear in all eight episodes of season 1, focussing on the hero’s fights with the spiderlike Kikimora, cursed Striga and the fire-breathing dragons. The team also designed epic battles and the fiery, climactic sequence. Led by VFX Supervisor Aleksandar Pejic, Cinesite’s artists worked with production supervisor Julian Parry.

Working together they took some creative approaches to VFX animation that make The Witcher’s creatures stand out. Incorporating them into shots and live action was also seldom straightforward and called for clever problem solving.

Based on ‘The Witcher’ series of books by Andrzej Sapkowski, the show is set in the fictional medieval place called The Continent where the stories of the solitary Geralt, the sorceress Yennefer of Vengerberg and princess Ciri of Cintra converge. Cinesite’s artists created the opening fight sequence of the first episode, in which Geralt confronts a massive, powerful spider creature, the Kikimora, in a dark swamp.

Looking for a Fight

The team researched the movement of real spiders to create a convincing, coordinated style of movement for the eight-legged creature, which needed to be dangerous but exact. They also needed to carefully match the movement of the Kikimora to the planned moves of the fight choreography, in order to create realistic interactions with Geralt. “Animating an eight-legged creature, splashing around in a swamp while fighting Geralt was a complicated task,” Aleksandar Pejic said.

“The choreography had to be really locked down before we could ‘dress’ each shot. Keeping the legs looking tidy without hiding Geralt, but still functioning realistically in a fight scene, was critical. Too much action would just lose the viewer in a frenzy of legs. The team began blocking out the Kikimora sequence back in February 2019 and we had our last Witcher shot finalised in November 2019, adding up to a good nine months of solid animation work with a team of approximately six animators.

“In terms of animation direction, while our work needed to fit naturally into the fantasy Witcher world, we were given a lot of freedom to explore the movement of the creatures. When there is no real-world reference for a fantasy creature, everyone will have a slightly different notion of how it should move, making it both a challenging and a collaborative process - the end result was a fusion of many ideas.

“On top of all that, the animators had to take into account the water simulation. Moving a leg too quickly might cause distracting splashes. Finding the right balance while fully interacting with our hero was complex, and just to make it a little more challenging, the editors constantly kept us on our toes as we amended and refined the animation to an evolving edit.”

Building an Army

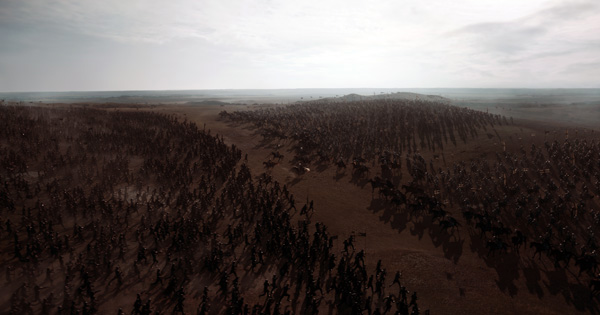

For another quite different battle sequence, filmed on a hillside outside Budapest, Aleksandar and the team built 10,000 Nilfgaardian soldiers to fight the Cintrans. About 20 extras were shot on the hillside location as reference and captured with 360-degree photogrammetry and motion capture cycles, as infantry and on horses, with a range of armour and uniform.

To turn the extras into an army, they produced 16 crowd shots using Atoms Crowd system software, integrated into Maya to work in their pipeline to simulate the army. “It was the first time we had used this crowd system and it worked well. The extras shoot on the hillside not only gave the team the digital elements for crowd agents but also the scale information, lighting and texture for compositing, plus movement reference for the animation,” said Aleksandar.

“Before beginning work on the actual shots, our Senior Crowd TD Gina Pentassuglia set up the agent, including variations, such as body type, armour and so on, and the control of the feet on the terrain. She then created a library of animation clips, including some from mocap sessions as well as our shoot, and worked on a shot creating a single, large heightmap based on the given environment.”

Once the initial crowd formation layout was chosen, she began laying out the choreography. Using curves to direct agents’ paths, she connected weapons to knights and riders to horses, creating variations in the knights’ posture and weapon rotation. In one of the shots, the knights came very close to camera, calling for the addition of facial blend shapes to create variation.

When she had approval for one shot, Gina exported the simulated crowd using Atoms cache functionality, which meant she could send her cached results to Cinesite CG generalist Hugh Johnson and the lighting department.

“Hugh could open the caches in Houdini using Atoms nodes and simulate flags, cloaks, knights going through fog and dust, attaching flames to the torches and arrows,” Aleksandar said. “Later, the cloth simulation was directly connected to the crowd in Gaffer via Atoms’ graph node.” Gaffer, open source software for look developers, lighters and compositors, supports in-application scripting in Python and OSL that the artists and TDs can use to design shaders, automate processes and build workflows.

The lighting department then used Gina’s caches to light the crowd and to attach lights for the torches and flaming arrows. In the past for feature films, Cinesite has used proprietary crowd software, but Atoms is able to handle thousands of agents very rapidly and in a dynamic way without compromising performances, which suited this kind of project. Lighting the crowd in Gaffer was also very fast.

Mythical Creature

The 3D team also created the Striga, another creature that clashes with Geralt, and the golden dragon for the series. The terrifying Striga is not confined to the Witcher stories but exists in Eastern European mythology generally, as a vampire-like demon spirit – thin, haggard and zombie-like. Therefore Cinesite’s artists could research for reference from many sources, including modern horror films like ‘The Grudge’, ‘Mama’ and scenes from ‘The Ring’. “Striga needed to have an otherworldly feel but not be supernatural. She had to conform to real world physics but at the same time she had to be able to interact with the environment in some unusual and interesting ways,” said Aleksandar.

The production built a prosthetic costume for the stunt crew to wear for most of the action shots. Cinesite’s team augmented and improved the look of the prosthetics, but also created the creature entirely in CG for the physically demanding shots, which needed to intercut invisibly with the prosthetic version. The digital version also gave them a chance to be a bit more creative in the performance.

“Although blending live action and CG meant the team were, to some extent, bound by the movement of the actor, we wanted to push the capabilities of the Striga, which led to many motion experiments and tests,” Aleksandar said. “One of the most successful shots of the whole sequence involved Striga climbing onto the tomb, and was an accumulation of all the animation style tests we had undertaken, merged into a performance that still convincingly matched the live action. The camera is also fairly tight on Striga’s face, so her anguish and frustration at not being able to get back in her tomb had to be really clear.”

Rotomation and 2D Warping

The Striga sequence was a combination of about 80 percent 2D adjustments to the prosthetic suit, with 20 percent full CG Striga shots. The approach for the 2D shots was to get a full rotomation to use as a shape guide for more traditional 2D warping methods.

“The brief was mostly about slimming the creature down. The client was after a look that was unnaturally thin. To ensure that we kept consistent shapes in the body and limbs throughout the of motions, rotomation was carried out for each shot. We had two versions of the model – one that matched the prosthetic Striga, and one that was a model manipulated to the slimmer look required,” said Aleksandar.

This allowed us to UV project the plate onto the larger model in Nuke, and then transfer these textures to the slimmer model, giving us a procedurally slimmed image – Nuke’s UVProject node sets the UV coordinates for the object, allowing a texture image to be projected onto the object. In most cases this served as a visual guideline for manual warping but in some low movement shots, it produced a great result and became the final look. We also created a lot of locators from the joints of the rotomated Striga model, and used these to drive the tracks of simple spline warp shapes, saving us time on the longer shots in particular.”

Wild Fire

Another sequence at the climax of the series involved the creation of a fire, spread by magic, that engulfs a nearby forest. This effect was developed by creating a CG forest and dividing it into sections, which were further subdivided into even smaller clusters. Burn simulations were run on each cluster incrementally, reducing the overall render time and allowing the fire to spread from cluster to cluster in a convincing way. The result is fire accelerated by magic energy bolts coming from the hands of the sorceress Yennefer.

“The whole effect involved CG fire on a massive scale, which took a couple of months to create,” Aleksandar said. “The first month was spent entirely on shot set-up led by FX TD Evrim Akyilmaz. That solid foundation was vital and meant that making changes later on was much more straightforward. The second month was spent adapting the speed and look of the fire, as the client required.

“The fire progresses very quickly, spreading through magic but still realistic and convincing. The team divided the CG forest into sections, manageable chunks - background, midground and foreground - with smaller clusters within them, and each cluster had its own simulation. The midground and foreground were divided into seven sections and each of these was further divided into three to seven smaller clusters, depending on how many trees the section required. The fire started in the middle of the forest, burning outward into the foreground and background.

“Breaking the simulations down made rendering much quicker. Changes could be requested by the client and reviewed, even the following day.”

Smoke and Embers

The team did not only have the fire element to deal with, but also a smoke element in the foreground, midground and background, plus a foreground ember element. “We wanted the smoke to be lit underneath because that's how the smoke in a real forest fire would be lit,” said Aleksandar. “If you look in the night sky you can see the smoke is being lit by the fire. Using all of the fire, and trying to light all the smoke from that fire would have been challenging and difficult, and would take a lot of rendering as well.

VFX Supervisor Aleksandar Pejic at Cinesite

“Instead, the team scattered some points and did a little bit of point-light instancing. Each light would just flicker on its own – they had their own size and were placed randomly, but using controlled randomness. For example, in some certain areas the team wanted a tentacle-like look for the spread of the fire, not a rounded shape, but moving as little tentacles in between the trees. Each tentacle needed to be lit up, so the FX team placed points in the necessary areas. To do this the team used Houdini, rendered in Arnold.”

This forest needed to catch fire and burn in a very short amount of time, although it lay miles away from where the character Yennefer is standing. He said, “We also need to connect it to the fire effect in her hands and her performance. That was the biggest challenge. We started with a small section and once we knew how the fire needed to move, we started applying those effects to a bigger area.” cinesite.com

Words: Adriene Hurst

Images courtesy of Netflix