Janek Lender and Georg Engebakken from NVIZ talk about helping the production visualise major action sequences on Marvel film ‘Morbius’, from stunt performance to camera moves.

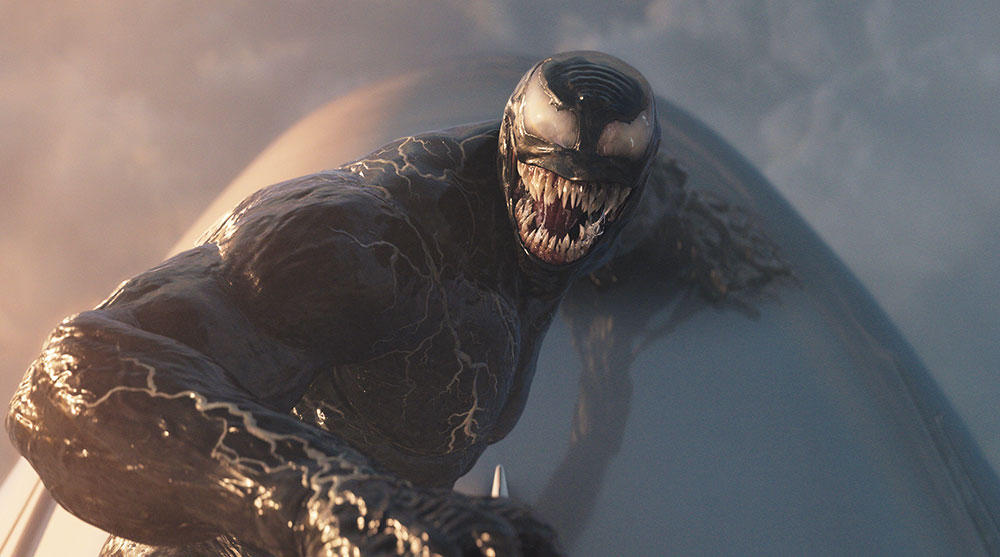

At the centre of the movie ‘Morbius’ is one of Marvel’s most unsettling characters, Dr Michael Morbius, a brilliant doctor who suffers from a rare blood disease. In search of a cure, he experiments with the vampire bats of Costa Rica. When he finally seems to have achieved success, he realises that he has inadvertently infected himself with vampirism, giving him dangerous powers that he is unable to control.

Visualisation was critical for the production, helping the Director Daniel Espinosa, VFX Supervisor Matthew Butler and Stunt Coordinator Gary Powell decide how the sequences should play out and what each one should look like. The team at NVIZ in London created previs and techvis for three major action sequences in ‘Morbius’, and delivered postvis for the film as well.

The NVIZ team, led by Head of Visualisation Janek Lender, worked with Matthew and Gary to plan the sequences ahead of recording motion capture for the stunts, carefully stitching together stunt action with digital takeovers at multiple points in the action. This not only improved the sequences creatively, but the detailed planning also led to cost savings on set. The director incorporated many of their suggestions into the production.

Capturing Stunts

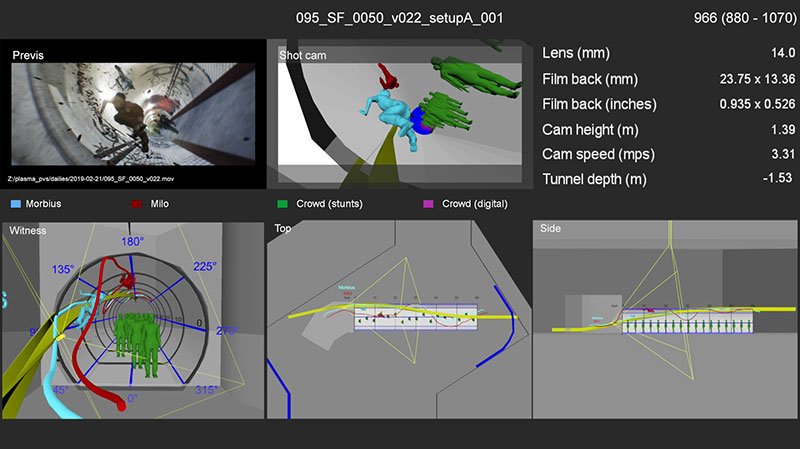

Because the selected sequences were driven by stunts, NVIZ were on board to capture those stunts in a way that allowed the director, Matthew and Gary to see the scene stitched together. Janek talked through their technique. “The motion capture here is used only as a basis for previs, using relatively low-end Perception Neuron motion capture suits, which can take a battering from the Stunt department,” he said. “We captured the motion of the stunt performers, who were on wires or rigs, and also shot their performances in situ with witness cameras.”

“Then, with the VFX Supervisor, we would discuss the takeover points, the full CG takeovers and the digi-double takeovers – and that would be what we put into the revis. We don’t advise on stunts or stunt performances, but just incorporate them into our revis to show them in situ, with CG takeovers or digi-doubles, so they can make more informed decisions,” said Janek.

“We cleaned up and used the mocap and witness camera data to produce a 3D digital version of the action, which we then pulled into our previs work in Maya. From there, we switched those stunts out and animated the takeovers that couldn't be physically performed, or in cases where the whole shot was going to be a fully digital takeover. At that point we can do whatever is needed for the action.”

Blueprint

The team worked over a long schedule on ‘Morbius’, in constant communication with Director Daniel Espinosa, “He was very hands on with the previs, as he was using it as a blueprint for what he wanted to achieve,” said Janek. Throughout the sequences, NVIZ’s collaborative work with the art department, the SFX and the Stunt team meant everyone was clear which department or departments were working on each portion.

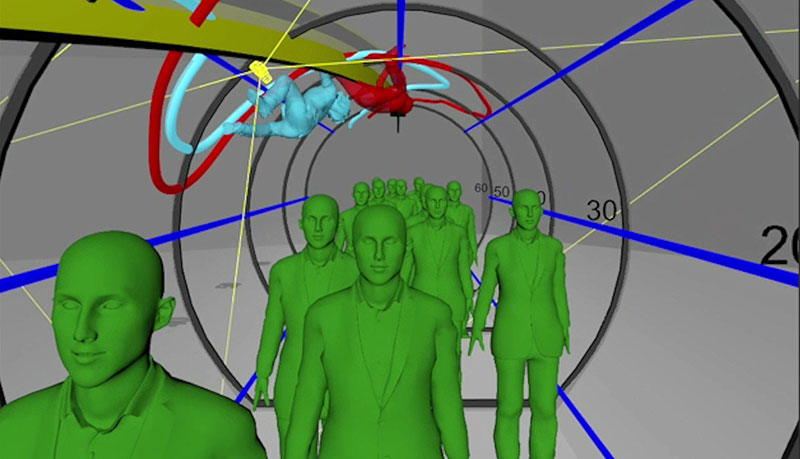

After previs had been ironed out, the techvis defined a very precise, accurate plan – with measurements, positions, equipment and so on – before the shoot starts to make sure that, after production is over, the VFX could happen exactly in line with the previs.

Janek said, “Previs is a sandbox for testing ideas in the same way that storyboards are. It changes through successive iterations and so is naturally part of the creative process. Techvis comes from the previs to help explain to the filmmakers the shooting methodology.”

London Underground

NVIZ’s process was especially effective for a huge fight sequence that takes place in the London Underground. Morbius chases fellow vampire Milo, battling with him through the crowds of busy commuters.

The camera follows stunt and CG versions of Milo and Morbius as they chase, fly and fight their way down escalators, through tunnels and onto platforms from a rollercoaster camera rig set up by the special effects (SFX) team. The NVIZ team, led by Janek working with Gary Powell, planned the previs for this sequence early on in production. They began by breaking it down into smaller sections, deciding exactly where the takeovers from live action stunt into a fully digital shot should take place.

This would help the other departments, including SFX and the Art department, to plan their own work. “The sequence was very well packaged and realised before the shoot,” said Janek. “Because of that, we could see that by filming the tunnel in the right way, we would only have to build half the set, which resulted in major cost savings for the Art department.”

Physical Sets

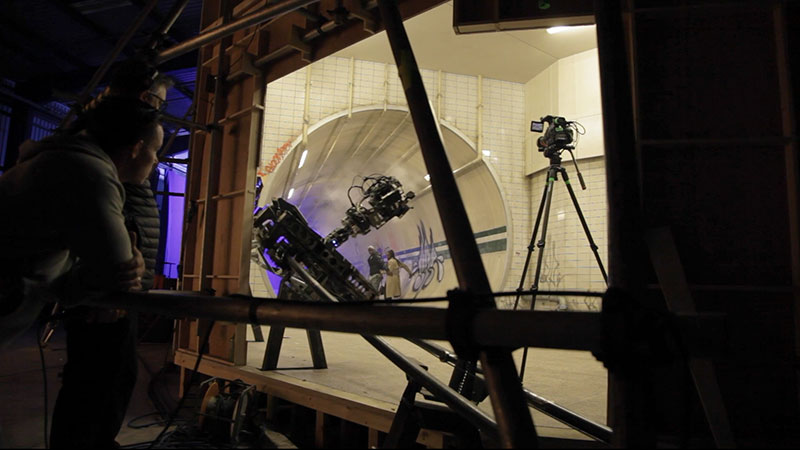

A section of the tunnel stage set was built in a warehouse in Wembley, northwest of London. When possible, other parts of the action were filmed in a disused section of the underground under Charing Cross, but some had to be created entirely digitally.

“We took plans of the physical locations that were going to be used, of the Underground and also the set build information from the portion of the sequence with a corkscrew camera move that was going to be captured on set. We stitched them together in our 3D software to make one long shot, which is what Daniel Espinoza was asking for. Using information about the camera at different points through those shots, we broke the sequence down into blocks and worked out which shots needed to be captured on set, which could be done on location and how that camera was going to create those shots.

The Right Way

“Filming the tunnel in the right way always hinged on creating the shots that the director was after, iterating on the camera work and on the animation until we got to something close to what he was really trying to achieve. We incorporated contributions from the Stunt department and the SFX department to break it down and put as much physical performance in there as possible.

“For instance, Gary would say, ‘This part could be where he gets thrown’, and the SFX Department could say, ‘This could be on a rail here and this could be a digital takeover’. So for us, the goal was very specifically breaking down what the director wanted to do, bringing all the departments together and making a plan of how to shoot it and to visualise what the director had in his head.”

In terms of camera work, it was very clear which parts could be handheld, and equally clear where takeovers to a different type of camera would have to be used. “That was how we worked out where takeovers could happen, and exactly where we needed to position the camera to take over from the next section,” Janek said.

“Even when shots became completely digital, the VFX team were never really on their own regarding the 3D camera because it was so meticulously planned around what the director wanted. There was another layer in VFX when they were just working with the director themselves and then they pushed the camera as needed.

“For instance, I’ve seen some retiming differences and changes. Obviously, when the shots become fully CG they could again control the camera, and do whatever they wanted with it, such as the freeze-frames that you see where they fly around the action. But because of the director’s singular vision of the evolution of the shot, it was very much driven from what we physically shot and then the VFX team added the impressive polish at the end in the final production.”

Corkscrew

The corkscrew shot was set up in a special way. A corkscrew camera move zooms in or out on a single line of sight while the camera rotates relative to the horizon or verticals in the shot, to create an unsettling, disorientating effect. The SFX team built a corkscrew rail around the subway set, with a hole cut in it so that the camera could stay inside the subway as the rail pushed it around.

When planning this shot, they realised they could save a lot of money by only building half of it and repeating the move backwards and making a join in the middle. Janek said, “That kind of choice saves costs for the rail, it saves costs for the set build, but it’s an aesthetic choice as well. So it’s making these big decisions and bringing all the departments together at the front of the movie. It helps creatively, to get them where they want to be quicker, and that saves them money and makes a better movie in the end.”

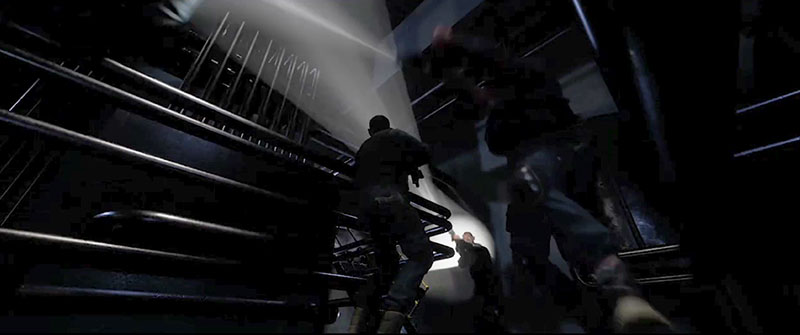

Container Ship

A couple of sequences critical to the story took place on board a container ship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where Morbius’ lab is located. This lab is where we first see him just after his infection with vampirism. Now transformed into a vampire, he breaks out of his cell. Armed troops try to hunt him down through the confined corridors of the ship, but the strength and speed of ‘superhuman’ Morbius prevent them from capturing him. The brief from the director was for several cuts of stunts and shots, conceived from Morbius’s point of view, to be assembled together into one long, dynamic shot that plays out across several locations on the ship.

To avoid a chaotic result that confuses the audience, the single shot was handled as a collaboration between NVIZ and the Stunt team, working from the same brief. Gary had chosen a few select stunts that he wanted to incorporate in that one evolving camera – in particular, when Morbius dispatches the ship’s crew members.

Janek said, “Once we had all the elements – including witness cameras recording stunt performances and rehearsals, and some motion capture as well – we physically stitched them together with all the takeovers from CG that would be in the free space, and that really helped us understand and define the camera and how it was going to be driven. It took a lot of iteration to get to where the director wanted it to be, but once we had it, we had a plan of how to put it together and how to shoot it.

Creative Contribution

The NVIZ team played a part in the creative development of the sequence as well, which needed to feel claustrophobic and sinister. Adding to the tension is the fact that Morbius is invisible to the camera when the soldiers view the havoc he wreaks through the ship’s many CCTV displays. This made the POV approach important, as well as marrying it together with the CCTV in a way that the audience could follow easily.

“In the final film, Morbius’s POV was used more than in the previs, so it was an idea that we put forward that obviously pushed all the way through to the finals. Once Morbius breaks through the sealed door, you can see him watching the crew while he’s crawling around somewhere among the pipes in the depths of the ship. Our team used the CCTVs intermittently to show action unfolding, but by the final, the concept was used as a way for Morbius to see himself and the monster he had become – in other words, it became a slightly different version of the same idea.

The action on the ship ends in another tense, violent fight sequence. For this one, the NVIZ team were given manga and early DC shows to reference. Like the London Underground sequence, the fighting is assembled of several different stunts interspersed and stitched together with digital takeovers.

They returned to the successful combination of the team working directly with Gary Powell and his performers to motion capture all the stunts. Once these were stitched together with digital takeovers to create the moves that were physically impossible, they went on to design the camera around them. The previs was used to anticipate and solve every potential problem before the shoot. The final result closely adheres to it.

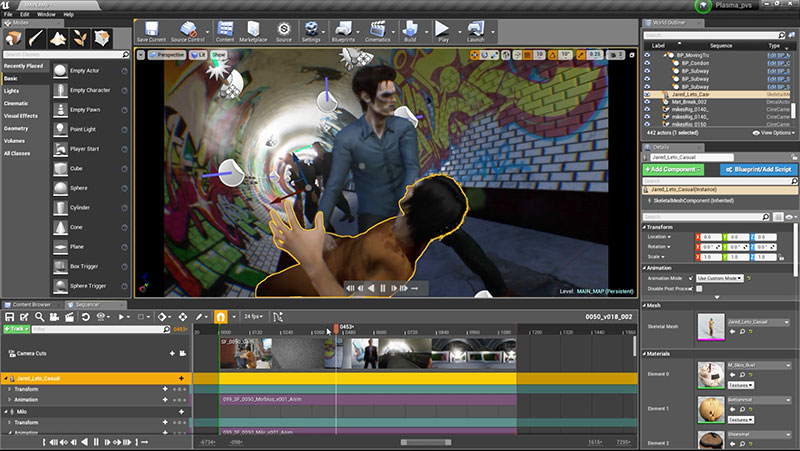

Real-time Pipeline

Finally, the scenes were pulled into Unreal Engine, where NVIZ’s Unreal Supervisor Georg Engebakken, would add live lighting, material changes and live environment changes. The result was a quick and iterative process that kept the director and department heads involved at all times. Georg said, “NVIZ first began using Unreal Engine on ‘Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald’. By the time we were working on ‘Morbius’, we were fully committed to Unreal Engine as our main tool for previsualisation.

“I joined NVIZ at that time as an ‘Unreal Expert’, having used it for many years as a games development tool and in my work teaching UE while I was an assistant university professor. NVIZ hired me to ensure that UE could be implemented smoothly into the pipeline, while being as artist friendly as possible.”

The first change this made to their process that was immediately noticeable is how useful real-time rendering is as a collaboration tool with the director. It gave them a chance to change locations of models and cameras, for instance, in real-time. If the director wasn't happy with a shot, he or she could guide them directly to the desired shot and see the final picture live on screen.

“This is something that can only be done in a real time environment,” said Georg. “On ‘Morbius’, collaboration was further enhanced by the fact that the editor was sitting next to the Unreal team. This nurtured a really nice workflow where we could very easily slot our renders directly into the master edit and very quickly see where we needed to iterate.

Building Blocks

“Our work on ‘Morbius’ helped tremendously to put the building blocks in place for what today is a very strong, robust Unreal Engine pipeline, which we have used on all our visualisation projects since, and will continue to use in the future but with a focus on Unreal Engine 5 and all the new features and strengths this new tool has.”

The whole project was a good demonstration of how carefully thought-out techvis and previs that are well integrated into the work processes of the whole production can inform decisions, support creativity and reduce costs. NVIZ's ability to allow filmmakers to quickly make decisions together at the very start of these processes, is where they can make the big calls that save a lot of the budget in the end. nviz-studio.com