Anyone watching 'The Shape of Water' knows that somehow, it feels like a romantic musical, even though the two lead characters are both unable to speak, let alone sing, about their unlikely romance. The answer to that puzzle is motion, sometimes live action motion captured in-camera, sometimes CG animations, sometimes a hybrid of both – but always relying on integrity of performance.

Mr X was the sole VFX vendor working behind the scenes for this movie, handling approximately 600 shots with a team of 200 artists. They worked on the project for roughly nine months, starting once the shoot was underway. They completed digital environmental work to recreate the cityscape of Baltimore as it was in the early 1960s, hero CG water effects at key moments in the film and delivered heavy damage to a classic Cadillac sedan, but the most intriguing and dramatic part of the project was enhancing the on-screen look of the face and body, and the facial performance, of the Amphibian Man, the true love of the story's heroine, Elise.

Amphibian Man

Discovered deep in the South American jungle, the Amphibian Man arrives unannounced one day in a sealed capsule of murky water at Occam Aerospace Research Centre in Baltimore where Elise, who is mute, works as a cleaner. Misunderstood and maltreated, regarded as nothing more than a politically useful specimen, his life is soon in danger. But meanwhile Elise recognises in him a kindred spirit. The two of them somehow communicate perfectly without words, and fall in love. Elise and her friends conspire to rescue him from the Occam lab, and a long series of funny and tragical adventures follows.

Well ahead of pre-production, the film's director Guillermo del Toro had spent about four years working on the Amphibian Man character. He designed a physical suit, which was built in latex at practical effects company Legacy Effects, and experimented with dry-for-wet photography, both of which allowed him to keep as much action and performance in-camera as possible. He strongly believes in capturing practical assets, looks and, especially, performances on-set regardless of any intentions to use digital enhancement in post.

Guillermo's concept for realising his creature character, played by the actor Doug Jones, was first to shoot all scenes he appears in with Doug on the set with the other actors, wearing the costume. Then, in post, he and the CG artists and animators at Mr X determined how to proceed with enhancements to the face and body on a per-shot basis.

True Romance

Mr X's CG Supervisor Trey Harrell said, “Doug is a tremendously talented prosthetics actor and mime artist. His performances in the costume, captured in the plates, were a great foundation for us to work from, both for the animation and the CG. When we started, Guillermo was still unsure of how much detail he wanted to show on the character. As production continued, he added to and altered the CG details until he eventually learned what his true vision was.”

The director's approach meant that the performances of the actor were always the driver and inspiration behind the facial and body performances in the film. Animation director at Mr X, Kevin Scott, described the overriding importance of romance throughout production and post. Because Elise and the Amphibian Man cannot speak, preserving their performances was an essential factor in conveying this romantic mood.

“We carefully studied how they performed together in the plates,” Kevin said. “This was my first experience working with a character in digital makeup, and was very aware that our job was augmentation of performance, not replacement. I now think it's going to be the wave of the future for many filmmakers. Augmentation means that a scene is actor-driven, and therefore under the control of the director. It also makes our job as animators somewhat different. We take a supporting role instead of a leading role.”

Facial Rig and CG Costume

Mr Xs work on the character was based on capturing accurate scans of Doug's face and of the latex costume he wore on set. It also required building a rig that could accurately achieve Doug's full facial range-of-motion, recorded through scans of his face performing poses corresponding to the Facial Action Coding System FACS.

This technique is a way of abstracting the data via individual muscle groups while keeping the creature’s performance grounded within Doug’s range of motion, even though the latex makeup he wore meant they could not see his actual facial performance on the day. They successfully used the scans as reference to recreate the emotional beats of the story.

Trey and the CG team built a full digital replica of the suit, allowing the digital artists and animators to partly or completely replace the character's body and performance, as required. For full-body work, accurate placement of bioluminescence effects over his body as he moved and dorsal fin augmentation, our team tracked his body motion by hand in 3D as a starting point,” Trey said.

Facial Tracking

Accurate tracking of shots was especially critical for recreating Doug's facial performance because conventional motion capture markers were not used. Kevin said, “Eyes were important as guides to lead the tracking because the latex of the makeup tended to work differently every day and would slide and bunch differently than skin does, so we needed a much finer degree of control than automated solutions could give us.. Audiences tend to look for a character's eyes first as well, so it made sense to work this way.

“The foundation of the facial performance was made up of three base tracking passes for eyes. The first showed the eyes only, as captured. The second showed the full face, accounting for makeup and eye fit on the day, and the third showed the full face accounting for sliding and pull, ensuring an idealized version of the creature’s silhouette.”

Decisions about exactly how, not only how much, to replace the latex of the costume and facial makeup had to be made shot by shot as well. Furthermore, while acting Doug wore one set of eyes that allowed more freedom of movement, but in the scans he would wear a more elaborate 'hero' set of eyes. Due to the importance of eyes, this called for more decisions.

Kevin recalled that in the early days of talking animal CG, it was very common to deform the original photography and apply it to an animal’s muzzle, for example, that had been animated with dialogue. “We used a modern update of this technique, at final compositing time in our case, to disguise the seams between the CG and the practical makeup as well as retain fine details from what was filmed, such as water droplets on his face,” he said.

At Home in the Water

As a potential means of capturing the character's graceful swimming performances in camera, Guillermo had spent time in pre-production experimenting with dry-for-wet photography. The technique finally used involved hanging up the actor with wires to allow as much freedom of movement as possible, and adding smoke to the set for atmosphere.

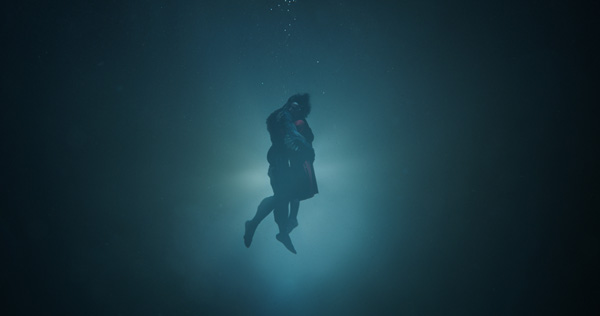

This worked for some underwater moves in some shots, but the creature’s full, free-flowing swimming action wasn’t achievable practically on a wire rig. He needed to appear entirely at home and at ease in the water, for which the animators used Olympic swimmers, sharks, seals and otters as real-world reference. Such shots were often entirely digital. Once the animation was in place, digital underwater effects – particle, bubble and volumetric FX - were added in post.

“We worked on the animation of his back fin as well because, similar to changes in breathing, it needed to express a full range of emotions, exhaustion and curiosity,” Trey said. Also, his charcteristic of blinking sideways is at first creepy, but once we get to know him, it is somehow endearing. “We took cues from nature. We all wanted the creature to feel that it was something undiscovered but didn't feel out of place. After all, this is our leading man. We took reference from alligators with their nictitating membranes, and could then add emotions and curiosity to him by varying the speed and offsets of the way the eyes opened and closed.”