'Baby Driver' is the story of a talented young getaway driver with an unusual hearing impairment. However, his love of music turns this weakness into his greatest strength – when he has the right song playing, he's ready to take on the most daring heist, leading him into some risky adventures.

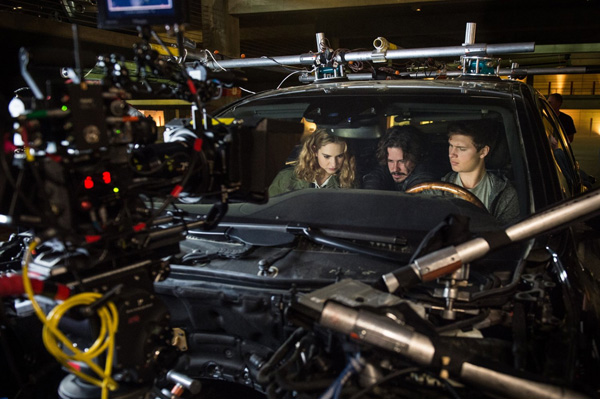

The film's writer and director Edgar Wright didn't envision 'Baby Driver' as a VFX-heavy film. Its story is told mainly through a dynamic soundtrack, thrilling car chases and harrowing gun fights and stunts, and while Edgar wanted to achieve as much of the action in-camera as possible, he knew he would need visual effects to the support the vision he had in mind.

After working with Double Negative on 'Scott Pilgrim vs the World', 'The World's End' and other projects, he chose to work with their team again, led by VFX supervisors Stuart Lashley and Shailendra Swarnkar. Edgar didn't have a big VFX budget, but planned the project carefully. As music was an integral part of the story and would be a foundation of the production, he chose the music for every scene, and not only storyboarded each sequence in detail but also made his own cut of the entire film as an animatic.

Vision in Motion

Edgar's early talks with Double Negative's team were more about what was needed to enhance and support the stunt work, camera work and looks, than about spectacular visual effects. Audio synchronisation and the use of choreography in this film were essential ideas he wanted to pursue to make the story feel and sound as engaging and exciting as it looked. He wanted virtually everything in the frame to move to the beat of the soundtrack music. The result touches the audience at a different level than the choreography in a traditional Hollywood musical - nevertheless, it tells the story of Baby, an unusual hero for whom sound and music are a critical part of life, in a vibrant way.

In particular, the stunts and unusual camera moves and positions were to be largely real but in some cases would need VFX techniques to make them work visually. Stuart Lashley joined the project while pre-production was still underway, and worked on set at the principle shooting location in Atlanta, Georgia. The team completed 430 shots for the film.

Stuart said it was incredibly helpful to be able to watch the entire movie in its raw animatic form, well before production had started. “As well as all of the thorough planning, Edgar was very open to the team's ideas about how to make his shots match his vision,” he said. “As an example, he liked the idea of pulling in tight on a shining hubcap on one of the cars just as it started up and pulled away, and wanted a clear idea of how to rig the camera properly so that the shot could be cleaned up in post to remove it from the reflection.”

Stunts and Choreography

When it came to working out the audio synchronisation side of the project, the focus was on creating dynamic shots and sequences that contributed to the story. Consequently, the artists learned how to collaborate more closely with editorial than usual, sometimes working back and forth frame-by-frame as each team introduced changes and tweaks in the looks and timing. They all got quite good at working this way as post-production proceeded.

Double Negative also worked with the stunt team from early on. They carried out some test shoots and, by producing some bash composites to check the results, they could figure out how to make the stunts as effective as possible. Other work they did to support the stunts was 2D face replacements, especially on stunt drivers during the most dangerous chase scenes when viewers would be looking out for the hero and villains.

A choreographer was on set at most of the shoots, and the music was playing as the cast and crew worked through the sequences, shot by shot. The camera moves and the performances were aligned to the music as far as possible, but to enhance the effect, Double Negative added subtly timed events and animated effects in post. For example, from inside vehicles during car chases they introduced pillars or fence posts flying past the windows to beat of the music, and added carefully timed muzzle flashes and gun fire to the practical effects during the fight scenes.

Tuning the Tools

Such precise, entertaining timing would have been almost impossible to produce practically, especially given the number of car chases taking place in different locations. Once the plates had been shot, the best approach to enhancing them was to art-direct the look as an effect in post. The tools for doing this already existed in their compositing pipeline but they needed to strengthen the flexibility of the audio synchronisation in Nuke.

Stuart said, “Producing visuals to sync with audio is usually associated with animation pipelines, where all character moves and interaction depend on the artist. But in a typical VFX composite, you have the movement in the photography to work with, and don't need to think as much about synchronising the effects work with an audio track.”

Due to Stuart's work in pre-production to understand the requirements of the project, and to Edgar's animatic, they had a few weeks before the plates arrived to develop and refine the compositing tools they would need in Nuke. Their working relationship with Foundry helped tune certain aspects of the software. Also, because the shots and sequences were being updated very regularly, they needed to enhance Double Negative’s Nuke versioning control tools as well with a rapid response through the pipeline to make sure all artists were using the most recent versions of the audio at all times.

Harlem Shuffle

Stuart identified two quite different scenes that demonstrate the audio synch especially well. Because the team were referring to their sequences by the name of the song chosen for the sound track, one of them was called 'Harlem Shuffle', when we see the main character Baby stepping out down the street to fetch coffee from a local cafe for his fellow partners in crime.

Not only Baby but cars, other sounds, passersby and visuals in the frame are moving in subtle ways to match the rhythm of this song. While everything was choreographed as far as possible on set, Edgar had the idea of adding graffiti to the walls featuring lyrics and imagery that also follow and magnify the music. Furthermore, the sequence was filmed as one long, single shot, moving along the street, which made tracking a challenge. Some of the tracking data had to be cached to make it manageable.

'Tequila' on the other hand was an intense, deadly fire-fight that relied on tight coordination of the special effects set-up for in-camera capture, with the visual effects in post. The shot design was based on practical guns going off in time to the music which, once it gets going, is a little like a machine gun itself, and so the edit was fast. From there, Double Negative added sparks, flying bullets and extra gunfire flashes, paying close attention to the song's intense drum riffs.

Perception and Story

The team learned that compositing to an audio track can work extremely well for a live action project, although it adds a challenge beyond the visual layers that compositors work with for typical live action shots. “We found there is a perceptual element that requires thinking about the audio, how it works with the visual story, and the emotional response it evokes from the audience,” said Stuart. “If making the audio-visual combination technically precise wasn't contributing to the story, or failed to deliver the director's vision, then the team would need to adjust the synchronisation and elements through various iterations to achieve a pleasing result.”

Stuart's VFX background is, in fact, in compositing, and he likes putting shots together manually in layers of different types of elements – multiple practical plates, green screen, CG and, of course, sound. It means he and the team can apply a problem-solving approach to challenges and adjust shots more quickly later on. This project was exciting for him because it had considerable scope for this kind of work.

Brighton Rock

The climactic sequence, named 'Brighton Rock' after the song, was a good example. It takes place in a working, multi-story car park in Atlanta, and begins with a car chase from street level to the top, all of which was shot practically at the location.

However, for safety and damage control, various shots needed to be put together in post-production. When characters are hit and knocked down by vehicles, Double Negative's team shot the accidents in stages inside the same car park and composited the passes together into the complete shots, which gave them more control and realism. Then, when the cars reach the top level and crash through a set of cables, the team replaced the real cables with CG. Damaged windscreens drenched with water from hazard sprinklers overhead were also re-created digitally.

The ultimate moment comes when one car falls from the top level through the carpark's central atrium to the bottom and catches fire. This required setting up and shooting a shorter, safer fall using a real car on a crane, but in a different area of the carpark, to comply with the owners' requirements. A set extension for the shot was created from a Lidar scan of the atrium, and an intermediate CG shot had to be built and inserted to lengthen the drop while swapping the real car out and in. The audio synch work was used to match the pulsing emergency lights flashing onto the CG, flaring headlamps and fight effects to the pacy sound of the music.

Camera Work

The main plate photography for 'Baby Driver' was shot on film, on Arricam and the Panavision Panaflex Millennium XL2, but other cameras were used for a handful of specific shots that included the ARRI Alexa Mini and XT Plus, mainly for the intense stunt work and the unusual camera positions the director wanted to use. Also, some footage was shot in anamorphic format, some in Super 35, employing many different lenses. Stuart remarked that these variations don't create as much extra work in post as they once did. Once a mastering format had been chosen for the project, they could set up a process at ingest to keep their work in a compatible format.

Interestingly, the special look of Baby's flashbacks to his childhood relied on in-camera film effects, not the work of Double Negative, and the retro look of his daydreams of happy times ahead with his girlfriend Debora was created in the digital intermediate at Molinaire. However, his memory of the collision from his past was a combination of shots of actors inside a car and SFX passes with a dummy running into the back of a truck, all brought together by the Double Negative team with extensive compositing. www.dneg.com

Words: Adriene Hurst

Images courtesy of Sony Pictures