Colourist Gareth Bishop talks about working with Baselight and director Jonathan Glazer to create a contemporary look for this film, pushing its dark story from history to the present day.

'The Zone of Interest' won the Best International Feature Film and best sound award at the 2024 Academy Awards, as well as the Grand Prize at Cannes and two BAFTAs, and has received over 150 further nominations.

The film explores the family life of Nazi commandant Rudolf Höss as he and his wife strive to build a comfortable world for their family in a house and garden next to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. Colourist Gareth Bishop at Dirty Looks oversaw the grade, which strongly influences the mood and atmosphere of the story.

Having worked with the director Jonathan Glazer on projects in the past, Gareth's journey with The Zone of Interest started early on in pre-production, assisting the cinematographer Lukasz Zal with technical camera tests and helping to analyse available light, before the shoot got underway.

A Colour Understanding

“I have worked with Jonathan several times as a grade assistant and we have a good relationship and understanding of one another,” Gareth said. “We have worked on a handful of adverts together as well as some short films. Our first film collaboration happened on Under the Skin (2013), when I was lucky enough to assist the late, very talented colourist John Claude on the grade.

“Jonathan is clear about what he wants and takes time to get the shoot right on-set, so the images look great when they reach me. He’s got an incredible eye.” Gareth noted that he stays involved with projects during post and that they always collaborate closely, as colourist and director.

“Jon had a very strong vision of how the film was going to look and what he wanted the end result to be,” he said. “He would share some ideas of what he was looking for and give some guidance, and then leave me to work while he focused on other critical areas, like sound design.”

Natural and Contemporary

The primary objective of the grade was to maintain a naturalistic aesthetic. Gareth aimed to capture the essence of each scene – from the opulence of a party sequence, with its high ceilings and strong reds and golds, to the closed-in, sombre tones of Auschwitz.

“We didn’t want it to look vintage,” he said. “The production design, costume and the content of the film place the viewer in the 1940s – not the look of the film. We wanted it to feel natural and contemporary, so the viewer felt as though they could be standing there, in that garden.”

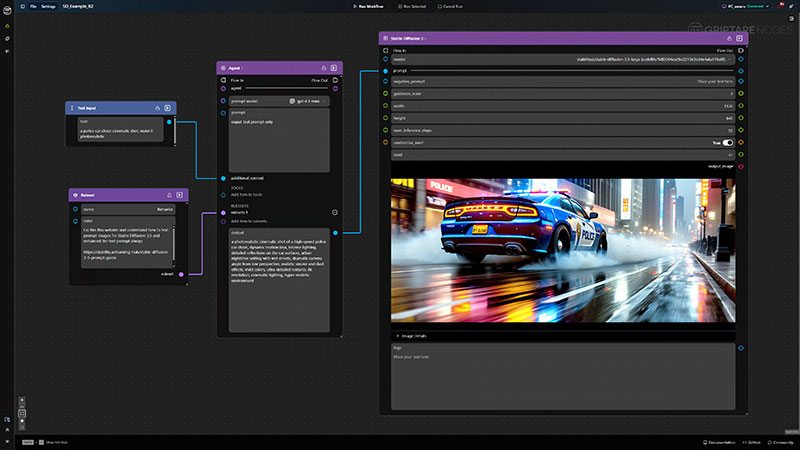

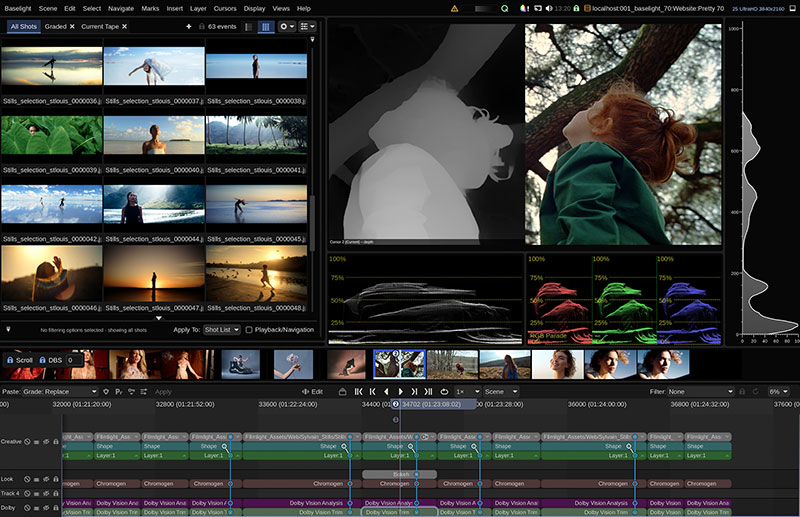

Working on a FilmLight Baselight grading system, Gareth used a combination of techniques to achieve the desired look. From adjusting exposure and saturation levels to delicately balancing contrasts, every decision was guided by a commitment to authenticity. “Since Jonathan doesn’t use visual references, it’s more about how the film should feel,” he commented. “We didn’t want anything to feel faded, it was important to get that separation between look and feel.

“For instance, establishing a contrast between the locations was vital. It took a long time to get this aspect right and we were constantly reviewing scenes in context with the rest of the film, to make sure we stayed loyal to the authenticity, and that it all worked together. Then we continued adjusting the saturation and exposure until we felt we had a good balance.”

Modern Cameras and Lenses

The film was shot on modern cameras and lenses, so one of his tasks was to take away any colour shift that the camera introduced as the type or intensity of lighting changed, or any other unnatural artefact, to maintain the feeling of realism. “The DoP shot only with available light and practical lighting used as part of the set design. We followed this style through into the grade,” Gareth said.

“We never shaped the images to alter viewers’ perception, and we didn’t use any keyframes, apart from in one scene. But for most of the film there’s no shaping, vignettes, no brightening faces – it’s all as it was shot.”

In contrast to a lot of modern films, Gareth steered away from creating a filmic look and instead set out to create a pin-sharp image. “We used a lot of sharpening tools in Baselight, to help achieve this effect and at one point I actually over-sharpened it,” he said. “Then we went through it and took the sharpening off anything that broke – using Baselight to draw shapes and carefully remove what we needed to.”

Ten Cameras, Shifting Light

The majority of the film was shot simultaneously through up to 10 cameras. Although that meant the angle could be chosen in post, it also created challenges – for instance, multiple cameras needed to be painted out from every shot. “In some ways, such as in the cut, it made life easier,” said Gareth. “But in other ways, including in the grade, it made things harder because it meant I had to do a lot of matching. In some scenes, the light never stopped changing, which would ordinarily be a nightmare – but as we wanted it to feel real and authentic, we were able to just let that run, which was nice.”

In one especially challenging scene, lead character Hedwig Höss takes her mother on a tour of the garden and meanwhile, the sunlight continuously changed. “The scene is actually only a few minutes long, but by the time they reach the end of the garden the sun is gone and the scene turns quite dark,” Gareth said.

“However, because we were not using any keyframes and trying to keep everything consistent, we had to expose the beginning of the scene to agree with the end of the scene. We got right to the end and Jonathan suggested maybe we should try using a keyframe, to pull it up or down half a stop and normalise the lighting over time. But we couldn’t do it – it just felt wrong.”

Rescue Mission

One of the most challenging parts of the grade for Gareth was a sequence shot entirely in night vision, which follows a Polish girl as she hides food for the people inside Auschwitz. He said, “The cameras it was shot on are not designed to shoot cinematic images and they came in less than HD. The challenge was to set these quite low-res images up against the 6K images shot on Sony Venice.” In full-frame mode, the full 6048 pixel width of the Venice sensor can be used to capture and trim widescreen images from the 3:2 aspect ratio.

To overcome this disparity in resolution, Dirty Looks asked the VFX company also working on the film, One of Us, to complete some tests and apply AI upscaling algorithms to sharpen the images. Taking multichannel EXRs into Baselight, Gareth used different versions of them to blend together, but then massively over-sharpened and broke a version of the images. This called for using the paint tool to paint back in some details into the final shots.

Gareth's determination and attention to detail paid off as he enhanced the footage, making sure that these shots integrated invisibly with the rest of the film. “It was quite a challenge to get them to stand up against the 4K images. We spent weeks trying to get it into shape.”

Fall Off to Darkness

Another challenging scene for Gareth was at the end of the movie, where a man walks through corridors that lead out into total darkness.

“The corridor walls had a yellow hue to them, which we had to take out, and as the corridors go off into darkness, they roll off into black. It was challenging to get that fall off right, without affecting the character in the scene. We didn’t use any shapes to pull up his face or anything like that, so getting the balance right on this scene took a long time,” he said.

“We knew what we wanted to do, but it was very hard to get it right. As soon as I got it, we knew straight away. I watched it play back and showed Jonathan, who said, ‘Yes, that’s it.’ This is one of my favourite scenes in the movie now.”

Gareth spent around eight and a half weeks on the aesthetic grade. “The highlight for me was getting through the film and finishing it,” he remarked. “It was tough, but we were lucky to have a lot of time and didn’t have the pressure of a tight deadline to work against, like colourists often do. A lot of our time was spent on the flare and night footage and then obsessively watching the film over and over again. No stone was left unturned in terms of what we could do.”

Through a combination of technical expertise and a delicate and strict creative vision, Gareth helped to create a natural, authentic film that has resonated with global audiences on many levels. www.filmlight.ltd.uk