The team from Digital Domain talk about building and destroying a complete 2.5 square mile chunk of New York City, and creating modern versions of Spider-Man’s favourite villains.

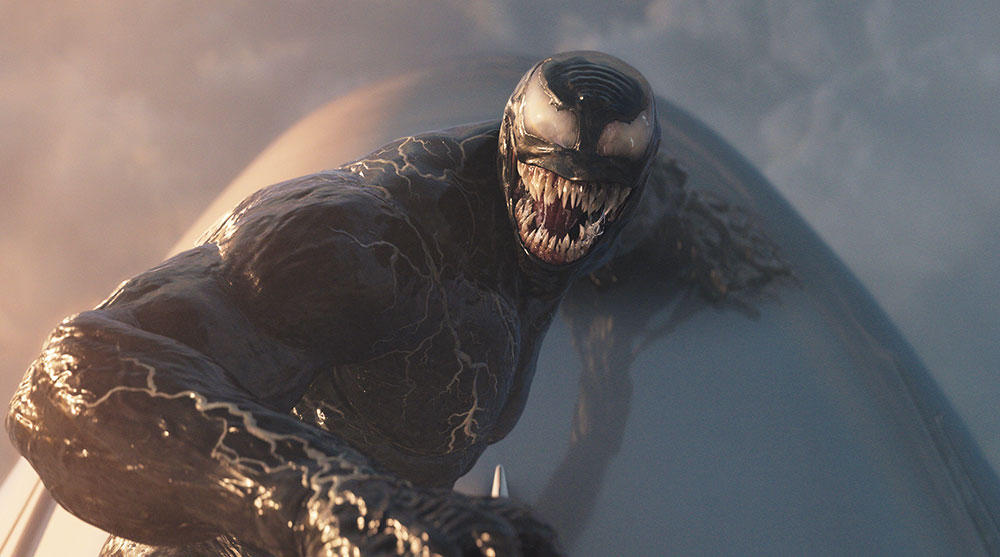

In Spider-Man: No Way Home, a miscast spell brings Peter Parker face to face with villains from the previous Spider-Man movies, who come back to haunt Spider-Man with new looks and powers, fuelled by sophisticated visual effects.

Among the worst of the villains is Doc Ock, aka Dr Otto Octavius, a mad scientist character armed with four powerful, almost indestructible tentacles. He appears unexpectedly on the Alexander Hamilton Bridge in New York City where he turns the motorway environment to chaos. Digital Domain was the VFX studio responsible, updating Doc Ock’s look, replacing and rebuilding his tentacles created for the 2004 film Spider-Man 2, and digitally constructing – and destroying – the bridge and the city in the background.

Digital Domain contributed over 520 shots to the movie, along with over 600 unique assets, including full environments filled with props, vehicles and crowds. By the end, the artists had also created 14 hero character builds and 19 digi-doubles for the film.

New York City

The work behind the sequence was massive and required Digital Domain’s artists to create 2.5 square miles (6.5 sq km) of New York City in order to give the filmmakers control throughout production. The team began by creating that entire environment, building a 3D version of the city as seen from the Alexander Hamilton Bridge, including digital versions of George Washington Bridge, the Harlem River and sky above, the pedestrian High Bridge, feeder roads leading to the bridges, railroad tracks and sections of the Bronx and Washington Heights.

Environments Supervisor Jon Green said, “The client supplied us with helicopter footage from around the Alexander Hamilton Bridge, along with LiDAR scans of the bridge itself and its immediate surroundings. Our environment team also imported OSM (OpenStreetMap) data into Houdini to get building footprints and rough height information. These datasets, captured mainly by overall VFX Supervisor Kelly Port and his team on location, established the basis of our environment build, with Google Maps and Google Street View giving more granular reference.

“Ultimately, everything needs to be a renderable asset, but the journey to that point often takes many roads. We had traditional hero 3D models, handled by our assets team, while additional props and large parts of the area were brought to life by the environments team. We also had 2D or 2.5D assets, which combine matte painting with 3D. The bridge surface where most of the action took place was handled as a separate environment by a team of modellers and texture artists.”

Aware of the need to keep the project manageable at render time, CG Supervisor David Cunningham explained that, rather than splitting out the scene by depth (foreground, midground, background), render passes were split into asset types and cardinal directions. “Trees, roads, static hero cars, moving traffic, characters and so on, were all rendered in their own passes, and then deep composited back together,” he said.

“Each of these elements were also more largely grouped into north, south, east and west areas, not only giving us better control over publishing from our layout and environment departments, but also keeping everything organised, which was essential for such an enormous area.”

Solaris Collections

Geography and infrastructure aside, props and the myriad little details of a living city are what bring the scene to life, including hundreds of thousands of trees, bushes, rocks and signs that the artists built and then distributed using SideFX’s Solaris look development, layout and lighting tools. Complete vehicles were built that would later be tossed around and digitally destroyed, with crowds made up of Digital Domain's existing digital assets and purpose-built digi-doubles.

David said, “The structured approach simplified our ability to define rule-based collections in Solaris. The consistent grouping of assets and regions was simple to set up on both the sequence and shot levels. We could group shots that had similar camera angles, for instance, and compile a list of those shots.

“Then, using Solaris' Context Options, we had the correct render passes automatically composed when the working environment matched any shots in that list. This took a fair amount of development effort initially, but became the backbone of our scene composition, allowing us to crank out the huge number of shots on the bridge.”

‘No Way Home’ was the first project that Digital Domain used Solaris on. The team has gained tremendously overall from the software and from USD workflows – everything from powerful instancing to multi-shot lighting workflows and publishing arbitrary assets and artist node networks. But it involved a considerable learning curve and became an evolving workflow. “In the beginning, it seemed daunting for artists to dive in and change setups, but the more we used it and the more we experimented, the further we were able to optimize and figure out how to improve our internal tools and approaches for the next project,” said David.

Scattering and Instancing

“Previously, we would have either scattered elements in Maya using MASH and baked out the full cache as an Alembic file. Or, in Houdini, we would have scattered assets and baked them out as Redshift proxies or published them as an Alembic layout. These methods had always presented a few problems when it came to making sure materials were attached correctly, and we would often have to create lookdev for multiple renderers.

“Using Solaris, we were able to take our lookdev’d assets, bring them into LOPs (Lighting Operators) and plug them straight into an Instancer LOP, giving us very fast, easy scattering results with the huge overhead savings you get from instancing. Inside the Instancer LOP, our environment artists created a SOP (Surface Operators) point-scattering system with all the control you’d typically have when scattering inside Houdini.

“This meant we could still use all of the traditional Houdini tools and tricks. Our team came up with very clever techniques for controlling variation of tree colours, scale, rotation and so on. Back up at the LOP level we could control further material variations and randomisation with the Solaris material variation node, and prune or cull based on rules or collections.”

This same instancing workflow was used to import layouts from Maya, facilitating the rendering of procedural traffic instancing for the thousands of cars that populated each shot, for example. It also allowed the team to make global changes over a large number of shots fairly easily. If the client decides they want every green tree to now be more saturated, or want to remove all instances of a certain vehicle from every shot in the sequence, the artists can make a small update to a template and run that through a group of shots via a single scene file, instead of updating every shot manually.

All the exteriors were then rendered through Solaris in RedShift, while the digital characters were rendered using Maya and V-Ray. By the end, when all elements were brought together, several shots contained over 30 billion rendered polygons.

Characters and Fight Animation

The action part of the New York sequence – the encounter between Doc Ock and Spider-Man – brought quite different challenges. Focussed on creating a new version of the villain based on the original from the 2004 film, ‘Spider-Man 2’, the team captured facial scans of actor Alfred Molina as the foundation for a digi-double that they would use in nearly every scene of Doc Ock on the bridge that did not include dialogue.

“Doc Ock’s original digital assets actually no longer existed,” David said. “The only reference we had was the previous film itself and a model of the tentacles Sony had displayed in one of their studios. We received scans of the practical model, but as you can imagine, there was a lot more to the job than that. The final asset was in the spirit of the original, but also incorporated modern ideas from the movie’s concept art, as well as from Digital Domain artists themselves.

Their animation was a key factor. Most of the team’s reference came from Spider-Man 2, and they were lucky enough to have Keith Smith, one of the original animators on that film, as a lead. Animation Supervisor Frankie Stellato said, “Once we established the overall look, we decided on ways to push the performance to suit our purposes.

Tentacles

“We looked for three main characteristics when animating Doc Ock and his tentacles. One of these was shape and appeal – a lot of opportunities arose where the tentacles’ motion could get confusing fast – plus weight and energy. We really wanted him to feel heavy and dangerous. When something moves with the agility and speed we had Doc Ock moving at, combined with his presence as a heavy, scary machine, it makes for some tense moments.”

To maintain total control over his tentacles, they keyframed all aspects of Doc Ock using a very detailed rig from Rigging Supervisor Eric Tang and team. Only his costume and hair were CFX driven. Interestingly, the idea of giving each tentacle an individual personality came originally from Alfred Molina himself, and made for a lot of fun on the animation side.

Frankie said, “Anytime animators are given the chance to add some personality to assets that would normally only be functional, we’re stoked to do it! We treated the two upper arms, Moe and Flo, as the brains of the tentacle operation. They would think and feel and emote when the opportunity arose.

“You can see little moments, such as when Doc Ock is chasing Spider-Man on the bridge, where Flo and Moe would stop, look and think to try and work together or plan where Spider-Man was going to be. Larry and Harry, the two lower arms, were treated as the muscle, there to assist Doc Ock as he traverses the terrain, and smashing and holding things for Moe and Flo and Ock to inspect.”

For the scenes when Doc speaks to Spider-Man, the actor appeared on set suspended on wires or an elevated platform. In post, the artists digitally replaced him from the head down and added the tentacles. Once the fighting intensifies, the digi-double version of Doc Ock takes over.

Digital Spider-Man

Along with Doc Ock, Digital Domain created a digi-double of Spider-Man himself, beginning with full performance capture of the actor, including body and face. On the bridge set, he wore a gray fractal suit covered in markers to help the artists add the metallic Iron Spider exterior that fans first saw in ‘Avengers: Infinity War’. The nested triangular pattern on a fractal suit gives abundant points that remain visible and trackable at almost any scale, even when the actor is moving fast.

“It’s always great to have good reference for the actor's body if you’re going to replace it with CG,” Frankie said. “In this case, however, we didn’t use straight motion capture because we weren’t shooting on stage, due to COVID. Instead, the fractal suit helped the matchmove team, as well as the animators, evaluate his performance better.”

The performances combined practical effects, including wire work and acrobatics by the actor himself, with digi-doubles in a way that shows off Spider-Man’s superhuman strength and reflexes. “We always try to keep as much of the actors' performance as possible, especially in a situation like this when we couldn’t rely on motion capture, so that meant matchmoving the motion by hand using a basic rig. That animation was then transferred to our hero rig and cleaned up, and then enhanced or altered by the animation team,” said Frankie.

Iron Spider

“For the Iron Spider we started with the asset from previous films, changing some of its details to match Tom Holland's current physique. We also changed the look development a bit to make the exterior more glossy, like car paint, so it would stand out on the freeway.”

Adding another layer of challenge, the lighting team then needed to match his lighting perfectly, because they were often using the actors' real head or face. Once rendered, these elements made their way to compositing, where everything was blended together into a coherent image.

A distinctive aspect of Spider-Man’s powers is his speed as he leaps around during fights, but such quick moves can easily make a performance appear weak or lightweight. Frankie said, “We had some really big shots that required a lot of mostly grounded actions, as we didn’t have buildings for him to climb onto or swing from. Any time things got a bit crazy, the animation leads – Chao Tan, Beranger Maurice, Keith Smith – and I would set up a meeting and go through some choreography that would make sense and avoid putting Spider-Man into full fast forward mode. We wanted to make sure his weight and proper follow-through on actions were all there.

Continuously Destructive

A large-scale, superheroic fight scene like this one can quickly become unreadable. Previz helps the team plan out the beats in advance, but along the way, story points may shift and shots get swapped around in the edit, so the artists have to stay on top of those developments to maintain continuity.

David described managing the simulations. “The ground, cars, barriers and so on were all simulated with rigid bodies within Houdini. FX artists Jie Meng and Ryan Hurd handled most of our destruction using a clever mix of soft constraints and glue for both the concrete simulations and the car denting and deformation, which happens when Doc’s claws grab and crush them.”

Bullet Solver RBDs were used for the concrete and glass simulations throughout the sequence, including FX Lead Eric Horton’s initial reveal of Doc’s claw as it crushes concrete right in front of the camera. The other FX lead Matt Rotman used Houdini’s Vellum for the bending and tearing of the overpass sign as Spider-Man is thrown through it, and as Doc Ock pulls up cars.

Some of the more interesting shots were the ones when cars get crushed. “It’s always a fine balance to effectively bend and dent metal without letting it look ‘soft’,” David noted. “A certain amount of creasing and harder edges are necessary to get the damage to look believable. We had one shot where a car, affectionately known as the ‘taco car’, gets folded in half as it is pulled through a hole created by Doc Ock. That was a fun challenge to solve. Thankfully, we had a ton of real world reference from Marvel’s senior special effects supervisor Dan Sudick and his team on set that allowed us to match real world examples.”

Nanites

During a conversation between the two characters, the nanites – small metallic, scale-like objects that power the heroes’ suits and other gear – that make up the Iron Spider suit are transferred to Doc Ock’s tentacles. Digital Domain worked with the filmmakers to create the critical ‘bleeding’ effect occurring as the nanites coat the tentacles and change their texture and colour.

Strange and subtle, the Nanite effect is based on two stages. A wire-like growth creates the framework for the new additional ‘scales’ that appear on the tentacles, and a secondary liquid growth fills out the volume of these scales and smooths down into the final form. David said, “The initial stage is growth propagation developed by Matt Rotman using a custom solver to shape the silhouette and wire framework. The second stage is a particle simulation that fills up the scales and is meshed as a particle fluid surface.”

The control of this required a lot of iteration to get the timing and art direction to work. As much as we could, the initial stages were procedurally driven to allow for adaptive changes. The Spider-Man suit transformation seen in a later sequence was achieved in this manner, using a noise-like growth pattern driving an initial particle fluid-surface layer followed by a secondary layer of instanced hexagonal pieces of geometry which would scale and settle into position.

Meeting

Peter Parker’s confidence is further dented when another villain from the past arrives, the Green Goblin from the 2002 Spider-Man film. This time, Digital Domain created a fully digital version of the character, starting with scans of the physical costume. By this point in the story quite a lineup of familiar villains has been re-introduced, and Spider-Man invites them to a meeting at the condo of his bodyguard Happy Hogan.

Along with Spider-Man, Doc Ock and Green Goblin, Electro and Sandman are present. Digital Domain again based the digital character of Sandman on a facial scan of actor Thomas Haden Church, but the animation team then keyframed the facial and body animation by hand.

David said, “Sandman was a careful balance of several components. At his core, he was a sculpted model of Thomas Haden Church, enhanced with muscles to match his comic-book origins and skillfully animated by our team. His base performance was inspired by reference footage of director Jon Watts, and the face was matched to Church’s voice performance. The tricky part was making sure that the performance and recognisable features shone through without being overpowered by the effects.

Motivating Sand

“We used maps and procedural masks to tone down the noise in the sand in key areas around the face, and would always have to art-direct where cracks could and should appear. Lighting and shot-modelling were a large part of this as well, to ensure we got enough facial and muscular detail in various lighting scenarios. Hard shadows could pull out detail in some cases, and in others plunge his looks into far too dramatic a place. It was always a complex blend of effects, shot-modelling, lighting and compositing to make sure that his look and animation performance were recognisable from shot to shot.”

The base level of the effects was driven, or at least initiated, by that performance from the animators. The animated body was then piped into a complex series of simulations, combining rigid body dynamics, vellum grains and particle simulations. They used RBDs to simulate the larger underlying portions of his body – larger scale movements that would drive the cracking and opening of the sand. These rigid bodies would then drive a grain simulation that formed the surface of Sandman’s body, and would fall apart in clumps and regenerate to fill the voids left behind.

Finally, additional particle simulations were run on top for specific art-directed falling of sand, usually in finer streams. “All of the motivation had to come from the animation – sand falling while unprovoked, or alternatively, areas not emitting sand when his arms rubbed against his body, for instance – would look strange. So we had to justify almost every part of the simulation,” said David.

With everyone in a less-than-friendly mood, a destructive battle ensues that bursts out of the building and onto the street. A combination of bluescreen and physical sets on a soundstage was captured in-camera, including parts of the condo, a small section of the hallway that could be redressed and reused to show different floors, and the courtyard. The rest was created by Digital Domain’s artists, including all the views of the street and surrounding city. In total, the team created half a city block in either direction, including the building itself.

Electrical Iterations

The battle is heavy on superpowers, calling for performances of both real stunt actors and digi-doubles. As well as the digital destruction caused by the characters battling from floor to floor, the artists also worked creatively to develop multiple options for the power effects. For instance, Electro looks quite different from his debut in the 2014 film ‘The Amazing Spider-Man 2’. Digital Domain developed several versions of his electrical powers, each showing varying levels of visual intensity, and then let the filmmakers decide.

David said, “Creating a brand new effect is always an iterative process, even when you’re starting with a base reference from previous projects or great artwork as provided by Marvel. Often it’s better to run a variety of simulations and quickly composite them, just to start the conversation, establish a visual language early on, get an idea of what people like and don’t like. Then we can start narrowing down our direction.

“Electro, like Sandman, was being developed by multiple VFX Studios in parallel, all under the direction of the overall VFX Supervisor Kelly Port. We knew that the look wouldn’t be what it was in The Amazing Spider-Man 2 and that director Jon Watts wanted to establish a new look for the MCU.

“For Digital Domain’s part, in Happy’s condo we showed a variety of tests, ranging anywhere from a character made completely of energy to just his eyes glowing. In the end we wanted to keep him subdued in this environment then have him charge up when he steals the arc reactor from the fabricating machine.”

Times Square

From the battle in Happy’s condo, a battered, maskless Spider-Man wanders into Times Square. To express the emotion of this moment in the film, the filmmakers wanted to add dramatic perspective, with sheets of rainfall and dynamic camera movements. However, shooting in and above the real Times Square is no longer feasible at any time of day or night, and drone photography is limited in NYC.

To give the production those dramatic options, Digital Domain recreated Times Square digitally, based on real-world reference shots, and then added the damaged hybrid Spider-Man suit. “Any VFX we created would need to keep the audience engaged. Since production couldn’t shoot or use drones to capture plates, our environment team built this section of NYC from scratch based mainly on photographic reference we found on the web,” said David.

“Like most of the other environments, it was a majority 3D build enhanced by 2D matte paintings, but the most difficult part of these shots was the rain. We needed layers and layers of dramatic rain that had to be lit by the city lights in the background as well as the huge foreground jumbotron. We ran what seemed like hundreds of rain simulations and gave our compositing team an unruly number of rain layers to work with. It was a massive effort to bring these shots to life.” digitaldomain.com